Review of the new TLA - Part two

Yesterday we started our review of the new TLA. We reported on the search. Today we’re talking about the hit list and the lemma detail page. Hang in there! There will be two more parts and our conclusion will be in the last part.

Hit list

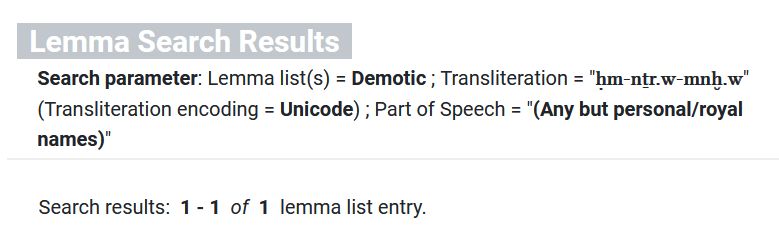

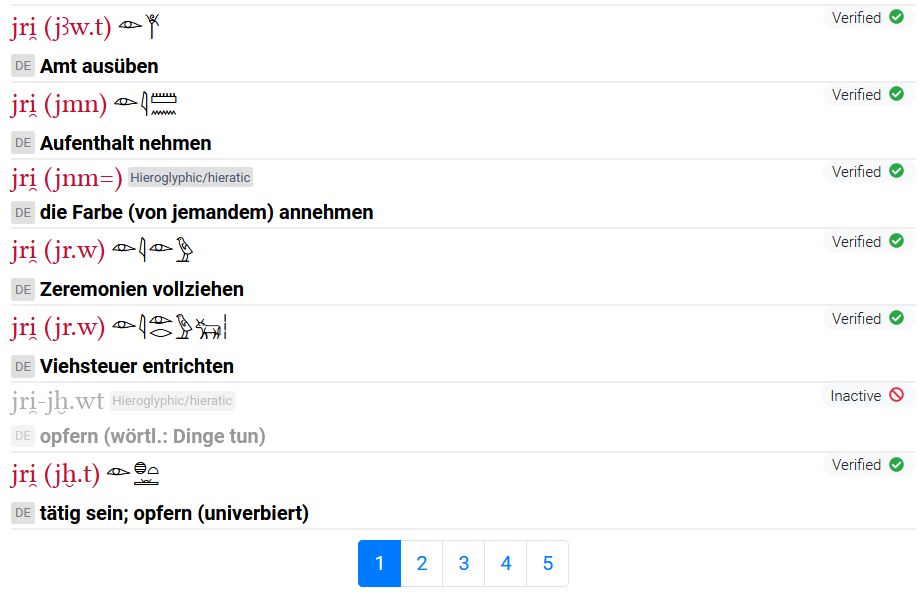

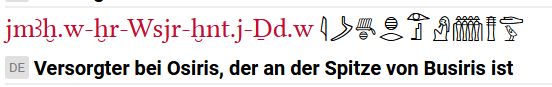

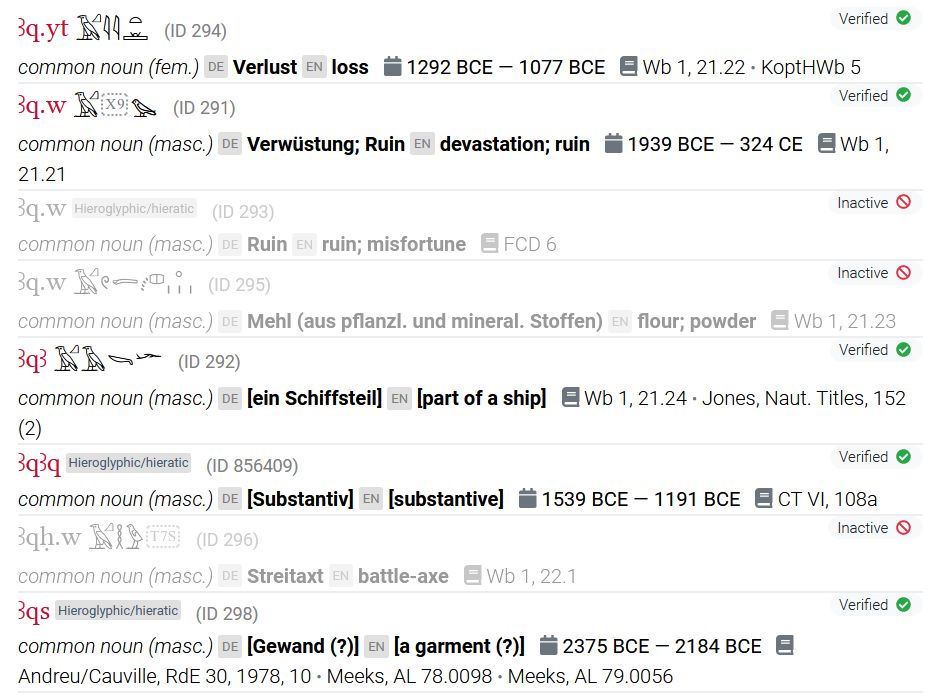

If you send a search on the search page, the hit list is generated. At the beginning the search parameters are listed. This is excellent! Thank you very much, that you can follow your search also on the page with the hits. The transcription appears - not only here, but always in the new TLA - in a font with serifs, while everything else appears in a sans-serif font. The mixture of serifs and sans-serif font creates a jarring impression. Some examples:

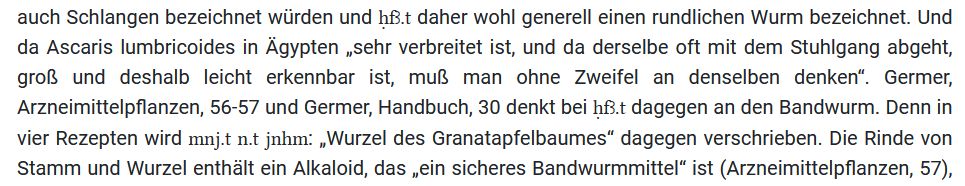

Below that, the number of hits in total and on this page is indicated. The number of hits per page is limited to 20. Therefore there is then a pagination for more than 20 hits, so that one can switch between the hit pages. Below that, the hits appear separated by a horizontal line. The hits are sorted by the Egyptological alphabet. Note that parentheses and hyphens play no role in the sorting. Thus, jri̯-jḫ.wt appears sorted between jri̯ (jr.w) and jri̯ (jḫ.t).  As a default, the following information is given for the hits: Transcription, Hieroglyphics, German Translation and Redaction Status. The hieroglyphs are in Unicode. Hooray! Unfortunately, our recommendations have not been taken note of. Variants are encoded as characters: https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/850775 has as hieroglyph 𓇋𓌳𓄪𓐍𓐍𓂋𓁹𓊨𓀭𓏅𓊽𓂧𓅱 instead of a 𓇋𓌳𓄪𓐍𓐍𓂋𓁹𓊨𓀭𓏃𓊽𓂧𓅱.

As a default, the following information is given for the hits: Transcription, Hieroglyphics, German Translation and Redaction Status. The hieroglyphs are in Unicode. Hooray! Unfortunately, our recommendations have not been taken note of. Variants are encoded as characters: https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/850775 has as hieroglyph 𓇋𓌳𓄪𓐍𓐍𓂋𓁹𓊨𓀭𓏅𓊽𓂧𓅱 instead of a 𓇋𓌳𓄪𓐍𓐍𓂋𓁹𓊨𓀭𓏃𓊽𓂧𓅱.

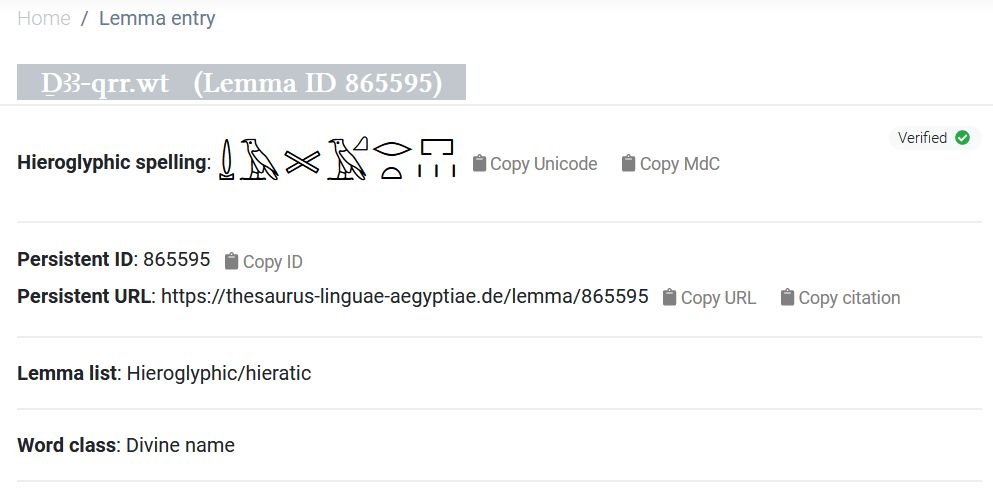

https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/865595 has 𓍑𓄿𓏵𓄿𓈎𓂋𓏏𓉐𓏥 instead of the correct 𓍑𓄿𓏴𓄿𓈎𓂋𓏏𓉐𓏥.

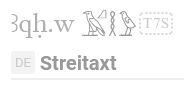

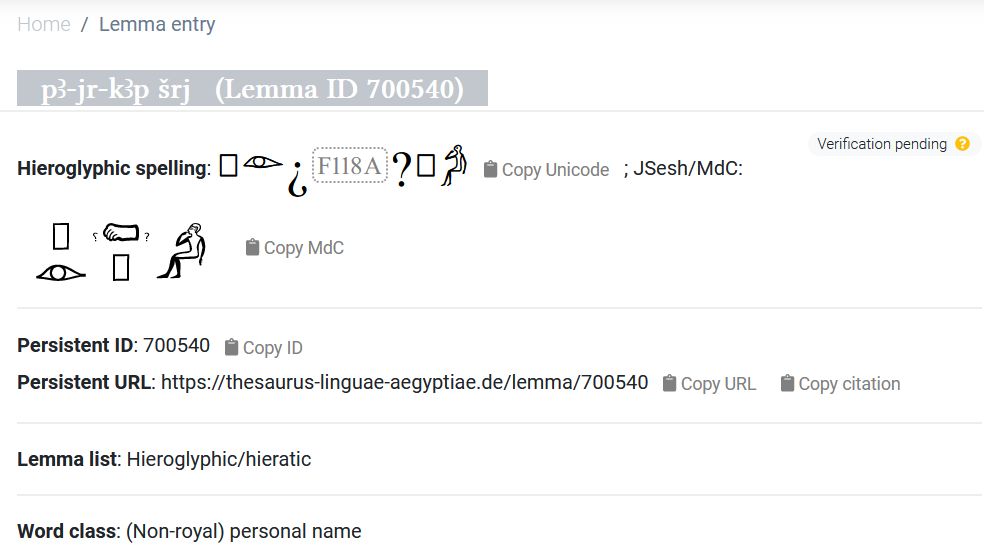

If there is no Unicode character for the hieroglyphs, the Gardiner number is placed in a rectangle with a dotted line.

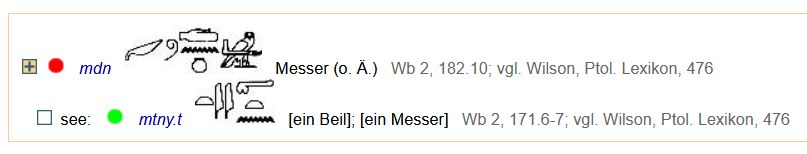

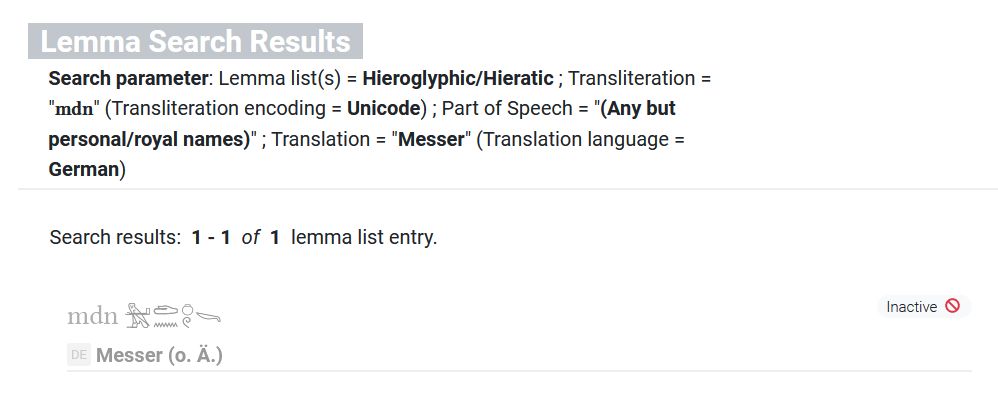

If you copy the hieroglyph characters from the hitlist, you get: 𓄿𓈎𓎛𓅱T7S. On the details page of the lemma, there is a special tool “Copy Unicode” that copies 𓄿𓈎𓎛𓅱<g>T7S</g> to the clipboard. Shouldn’t you expect the result to be the same? In any case, it should be 𓄿𓈎𓎛𓅱𓌏 at this point. The redaction status can take three different values: verified, verification pending, and inactive. The different redaction statuses already existed in the old TLA. There they were indicated by colored dots. The term “inactive” is misleading. It refers to the obsolete entries. These are entries which mostly originate from the Wörterbuch, but for which the Egyptological literature has determined that they do not exist in this form. For example, the mdn knife of the Wörterbuch is nowadays understood as mtny.t knife. The entry mdn is obsolete. Instead, the supposed occurrences for mdn must be posted to mtny.t. Therefore, the old TLA not only sets the mdn of the hit list to obsolete, but also associates the entry with the correct entry.

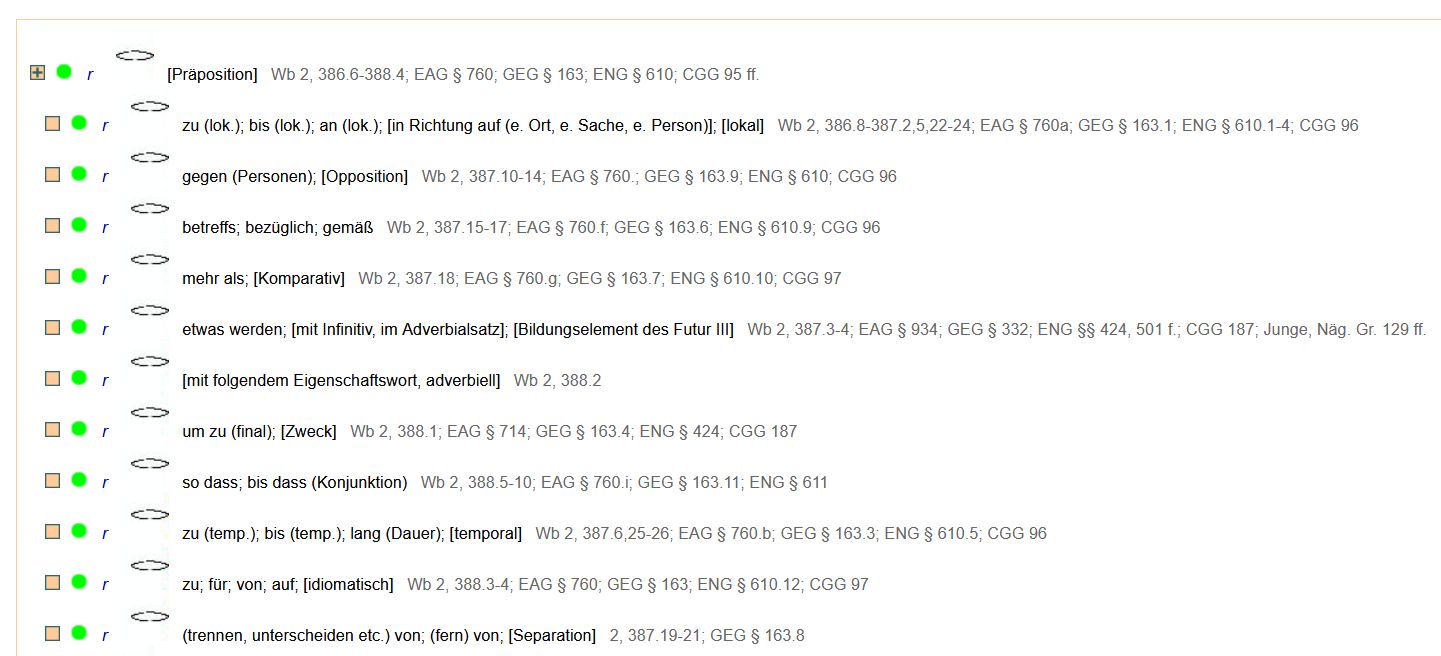

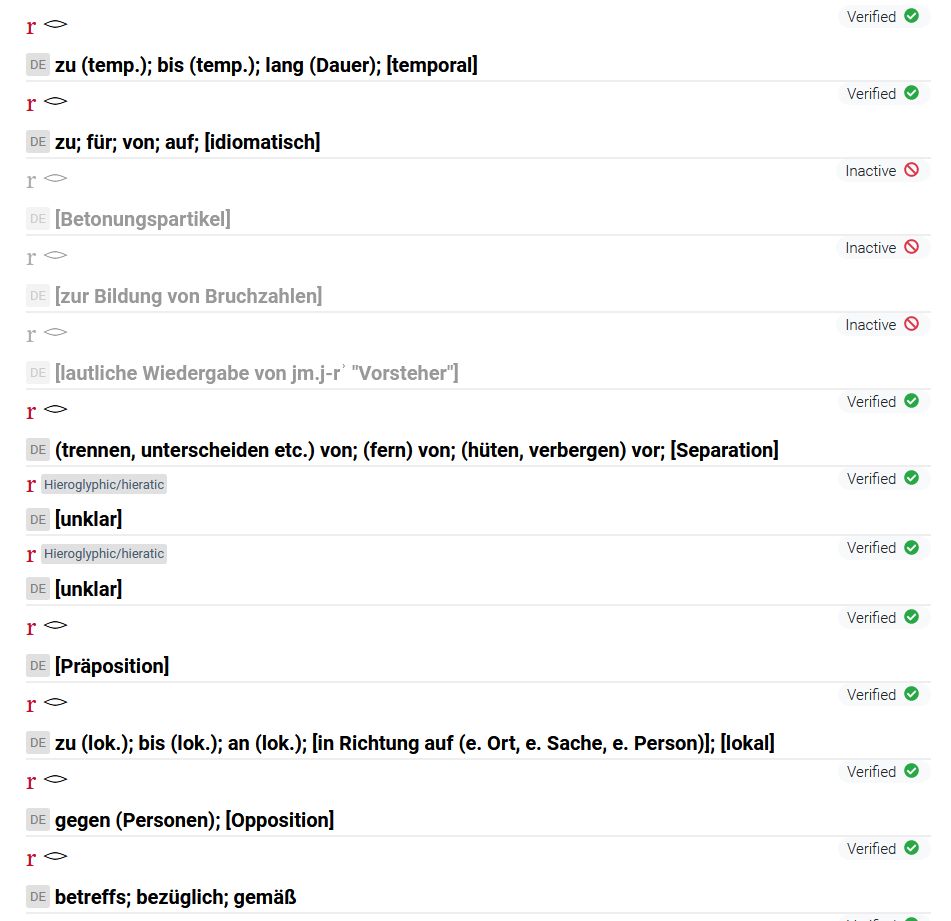

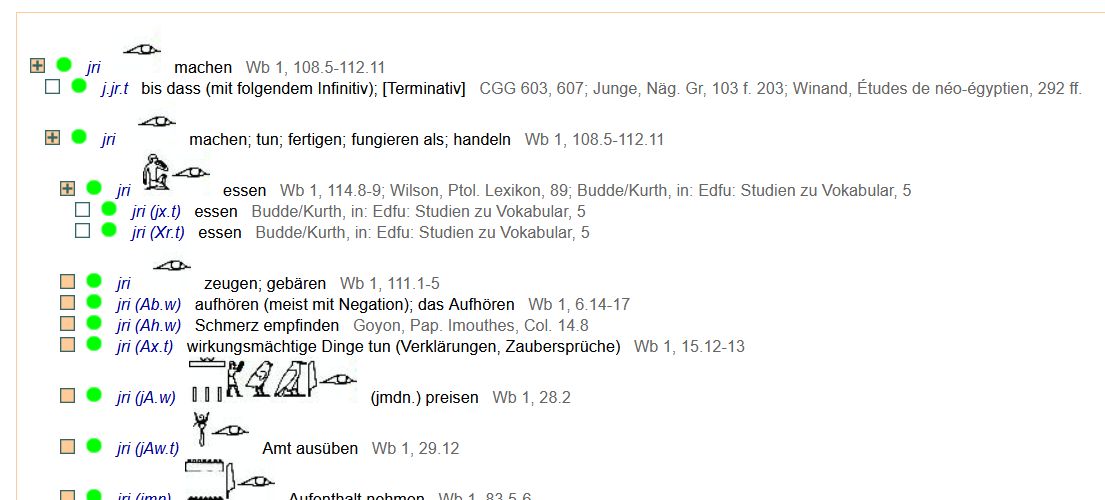

The new TLA omits this linking in the hit list. Instead, the obsolete entry is just grayed out.  This is a definite loss of user-friendliness. Furthermore, the hit list in the new TLA is always flat. All entries are on the same hierarchical level one after the other. The old TLA, on the other hand, offers not only the links from obsolete lemmas to regular ones, but also the hierarchical linking of lemmas, e.g. for prepositions and for verbs. The hit list clearly shows the relation of the main lemma r to the sublemmas.

This is a definite loss of user-friendliness. Furthermore, the hit list in the new TLA is always flat. All entries are on the same hierarchical level one after the other. The old TLA, on the other hand, offers not only the links from obsolete lemmas to regular ones, but also the hierarchical linking of lemmas, e.g. for prepositions and for verbs. The hit list clearly shows the relation of the main lemma r to the sublemmas.  This clarity is completely missing in the new TLA.

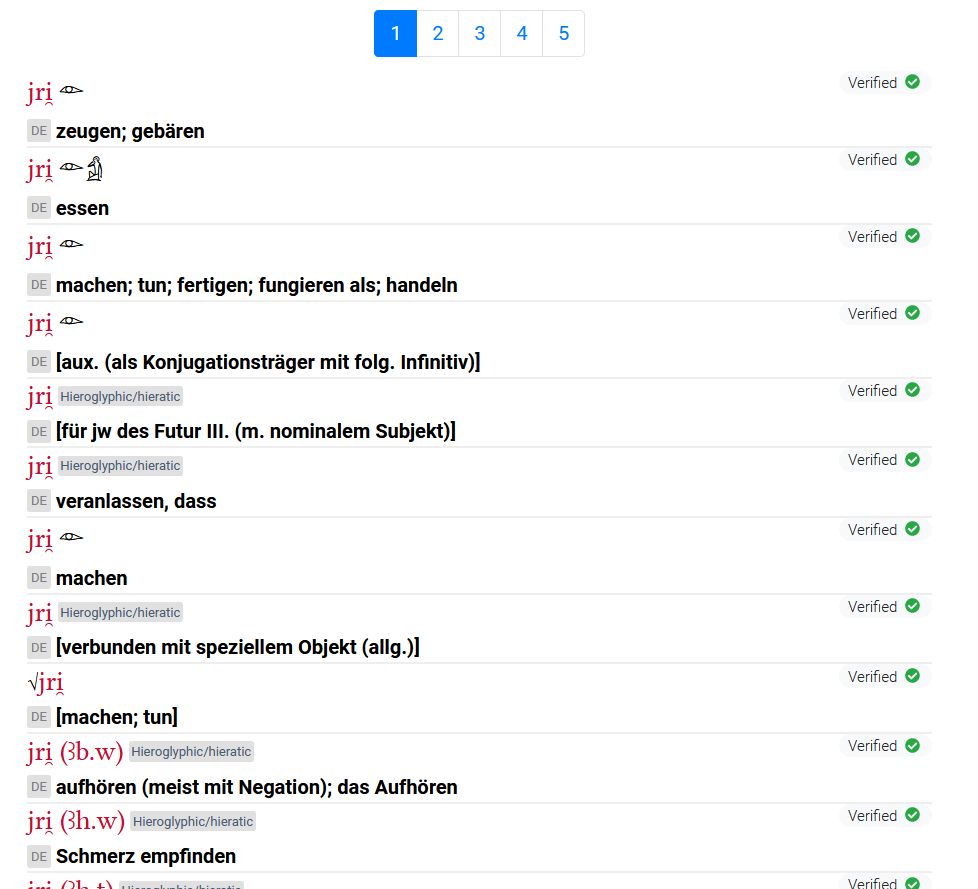

This clarity is completely missing in the new TLA.  The hierarchical relationship between lemmas is essential information that belongs in the hit list. Its absence in the new TLA is a significant step backwards. Other example: the verb jri̯ has numerous, semantically significant collocations that are listed in the TLA as independent lemmas (albeit subordinate to the verb). The hierarchical relationship of the lemmas, excellently seen in the old TLA, is not visible in the hit list of the new TLA.

The hierarchical relationship between lemmas is essential information that belongs in the hit list. Its absence in the new TLA is a significant step backwards. Other example: the verb jri̯ has numerous, semantically significant collocations that are listed in the TLA as independent lemmas (albeit subordinate to the verb). The hierarchical relationship of the lemmas, excellently seen in the old TLA, is not visible in the hit list of the new TLA.

If you click on a hit, you will be led to the detail page of the lemma. More about this below.

On the right side of the desktop you can modify the hit list. First of all, you can change the sorting. You can sort alphabetically, by the beginning of the attestation time and by the end of the attestation time, in ascending and descending order.

Then you can modify the shape of a hit. A hit must have only the transcription, any other information can be added or hidden. This concerns the hieroglyphics, the ID, the Word class (why is it not called Part of Speech here?), the German, the English and the French translation, the attestation time and the bibliographic information. Here is an example when all information is displayed:  As you can see, this is where the layout reaches its limits. The line breaks make the hits not very readable.

As you can see, this is where the layout reaches its limits. The line breaks make the hits not very readable.

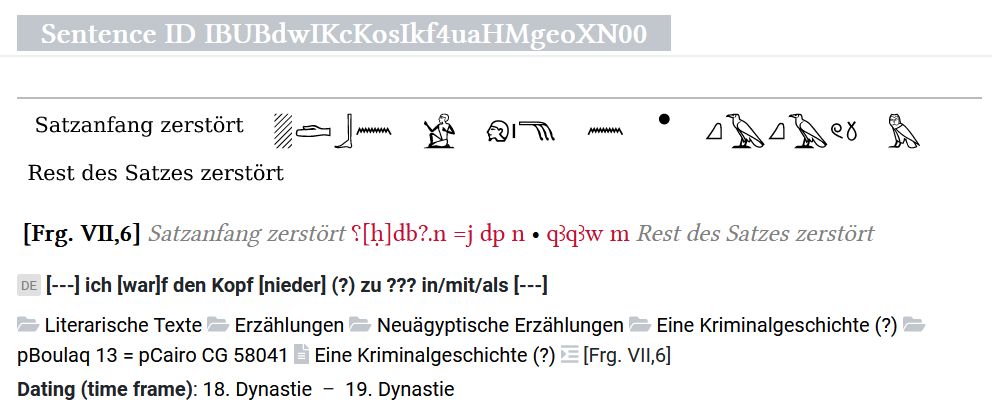

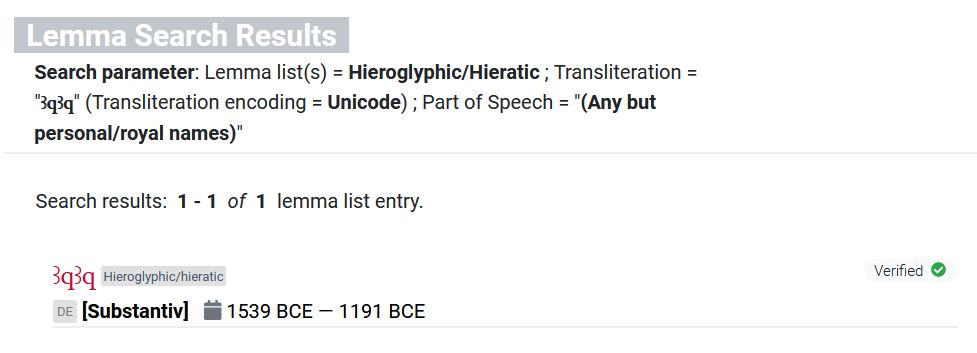

A word about the attestation time. In this form, as the new TLA offers it, it is not a meaningful lexicographic concept. It operates with absolute years (and then also BCE/CE instead of BC/AD). But an Egyptologist would rather think of dynasties and rulers. How does the new TLA get these absolute dates? The TLA takes all occurrences of a lemma, extracts the dating data of the records and converts them into absolute numbers. The minimum and the maximum of these data then form the attestation time. Example: the lemma ꜣqꜣq, which stands for a noun from the coffin texts, as the bibliographic citation CT VI, 108a makes clear, has exactly one occurrence in the new TLA: https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/sentence/IBUBdwIKcKosIkf4uaHMgeoXN00.  The text dates from the 18th-19th Dynasty. From this one occurrence the attestation time 1539 BC - 1191 BC is created.

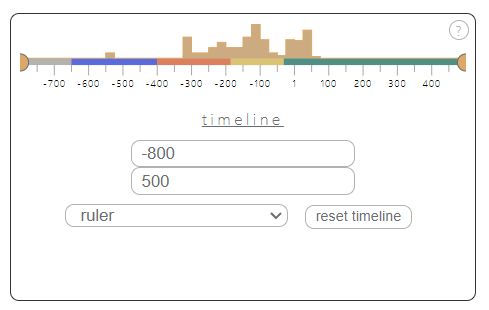

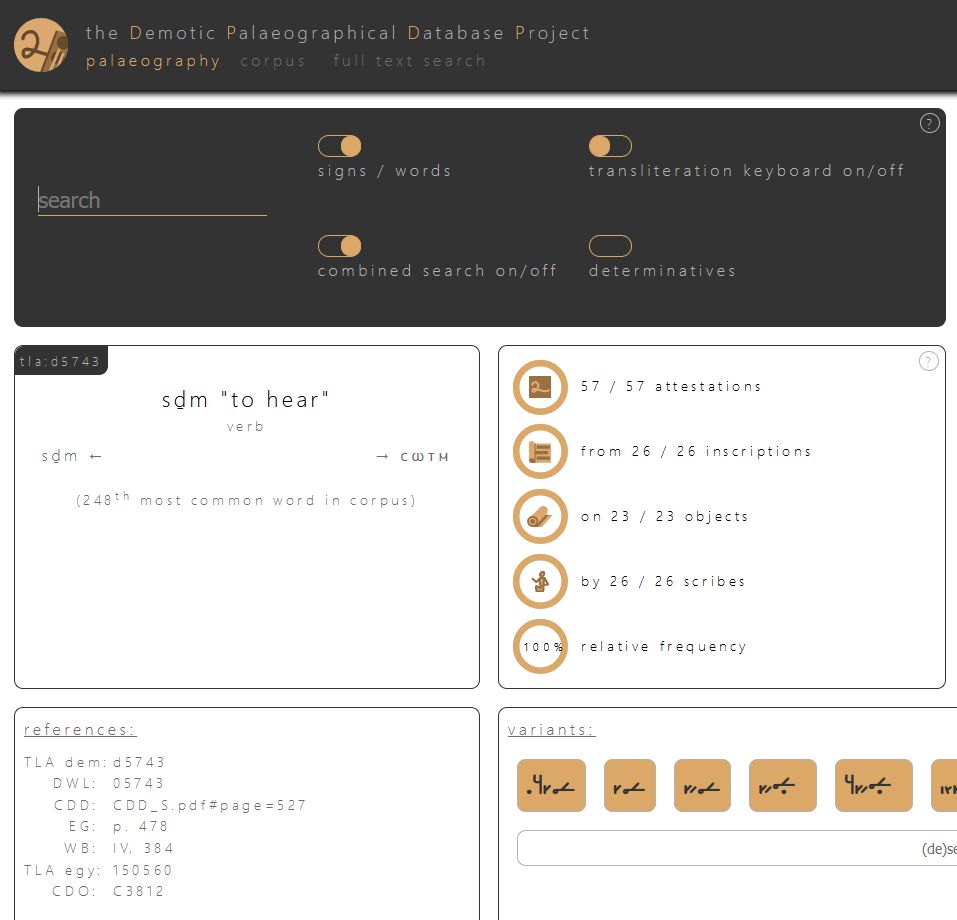

The text dates from the 18th-19th Dynasty. From this one occurrence the attestation time 1539 BC - 1191 BC is created.  The uncertainty of the dating of the text passage produces a very large attestation time. One could assume from the hit list that it is a more frequently attested word, since the attestation period is not short. Nevertheless, the attestation time is not long enough, since it is a word from the coffin texts. The Middle Kingdom is not even considered in this attestation time. But the worst thing about this concept attestation time is that it does not consider the distribution of occurrences at all. An attestation time does not map when a word is particularly frequently attested at a particular time. Accordingly, the representation of the distribution of the attestation times is essential for an evaluation. Other projects, such as DPDP, do an excellent job of this.

The uncertainty of the dating of the text passage produces a very large attestation time. One could assume from the hit list that it is a more frequently attested word, since the attestation period is not short. Nevertheless, the attestation time is not long enough, since it is a word from the coffin texts. The Middle Kingdom is not even considered in this attestation time. But the worst thing about this concept attestation time is that it does not consider the distribution of occurrences at all. An attestation time does not map when a word is particularly frequently attested at a particular time. Accordingly, the representation of the distribution of the attestation times is essential for an evaluation. Other projects, such as DPDP, do an excellent job of this.  In this form, the specification of a attestation time in the new TLA is simply nonsense, which has no place in reasonable lexicographic research.

In this form, the specification of a attestation time in the new TLA is simply nonsense, which has no place in reasonable lexicographic research.

There is also a separate help page for the hit list.

Lemma detail page

If you click on a hit in the hit list or enter an ID of a lemma in the search, you will get to the detail page of a lemma. The lemma detail page provides more detailed information about a lemma. This information can now be easily shared. On the top right there is a share button, with which this page can be posted on Facebook or Twitter or forwarded by mail. The transcription of the lemma with the following ID placed in parentheses acts as the heading. The headings of detail pages, i.e. also those of texts and thesaurus entries, are designed in the same way. It is always the name of the entry followed by the ID in brackets. This formal default is a bit strange, which is especially obvious for texts and thesaurus entries. More about this in the fourth part of the review! The following information is separated by the horizontal line which separates the entries in the hit list.

hieroglyphic writing

First, the hieroglyphic writing in Unicode is specified. This writing corresponds to the one in the hit list. After the writing, there are two buttons to copy the writing as Unicode or as Manuel de Codage. Note that the code after Manuel de Codage does not have to match the Unicode shown. Here is an example: https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/865595 has as hieroglyphic writing the already mentioned 𓍑𓄿𓏵𓄿𓈎𓂋𓏏𓉐𓏥.  According to Manuel de Codage, however, it should read U28-G1-Z10-G1-N29:D21-X1*O1:Z2. Unicode only gives the order of the hieroglyphs, but not the arrangement. This becomes visible on the page by using a font that uses OpenType ligatures. This is a highly recommended solution to deal with the arrangements. However, in Manuel de Codage these arrangements are hard coded. Thus, the information differs depending on the encoding type, since Manuel de Codage includes the lexicographically redundant information of the arrangement. Furthermore, the arrangement of the characters does not match. Why is the visual impression different from the information Manuel de Codage offers? In this respect, the code according to Manuel de Codage is misleading, and this button copy MdC is more disturbing than useful. If not all hieroglyphs can be displayed in Unicode, a graphic of the hieroglyphs is given in addition to the Unicode description. This graphic does not contain a facsimile but hieroglyphs generated with the program JSesh. The mapping between Unicode and Manuel de Codage is unfortunately not correct. In Unicode there is a

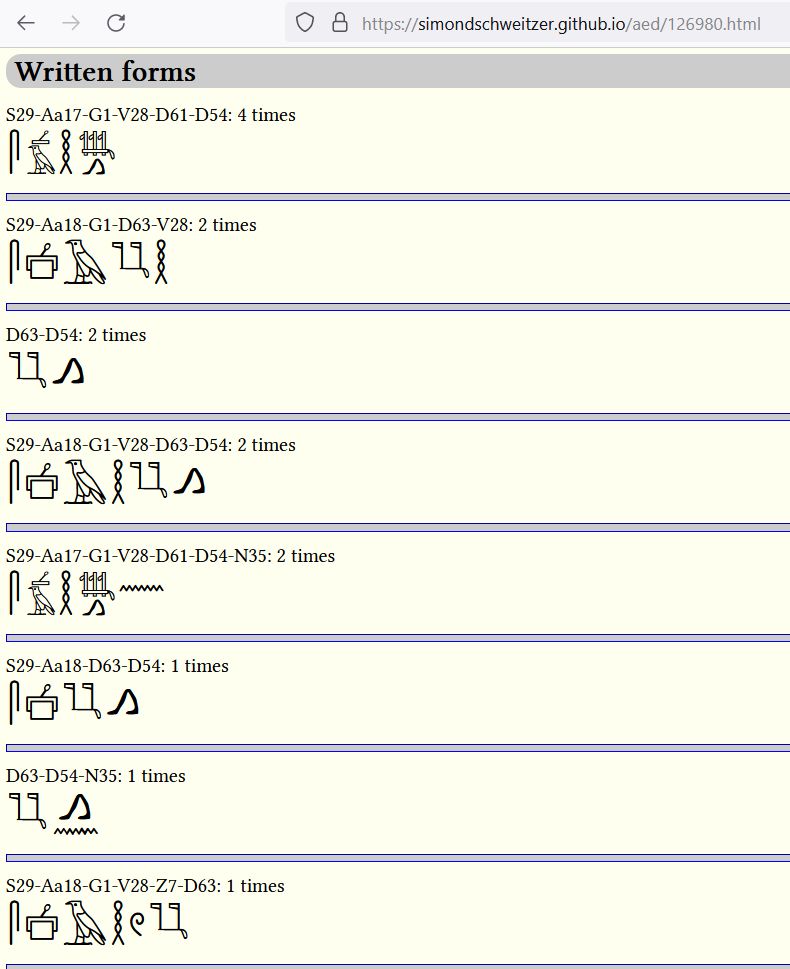

According to Manuel de Codage, however, it should read U28-G1-Z10-G1-N29:D21-X1*O1:Z2. Unicode only gives the order of the hieroglyphs, but not the arrangement. This becomes visible on the page by using a font that uses OpenType ligatures. This is a highly recommended solution to deal with the arrangements. However, in Manuel de Codage these arrangements are hard coded. Thus, the information differs depending on the encoding type, since Manuel de Codage includes the lexicographically redundant information of the arrangement. Furthermore, the arrangement of the characters does not match. Why is the visual impression different from the information Manuel de Codage offers? In this respect, the code according to Manuel de Codage is misleading, and this button copy MdC is more disturbing than useful. If not all hieroglyphs can be displayed in Unicode, a graphic of the hieroglyphs is given in addition to the Unicode description. This graphic does not contain a facsimile but hieroglyphs generated with the program JSesh. The mapping between Unicode and Manuel de Codage is unfortunately not correct. In Unicode there is a ¿, while in the image a ⸮ is used, cf. https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/700540.  Finally, the concept of a hieroglyphic writing is also to be criticized. It suggests that there is some kind of standard writing for a lemma. This is, of course, completely absurd. No one who studies Egyptian texts and knows the variety of ways a word can be written will want to uphold this concept. Normally, different writings are noted for a lemma, such is the case in the Wörterbuch, in Lesko, A Dictionary of Late Egyptian or in Wilson, A Ptolemaic Lexicon. There are implementations for this in the digital domain as well. The AED offers for a lemma all writings sorted by frequency.

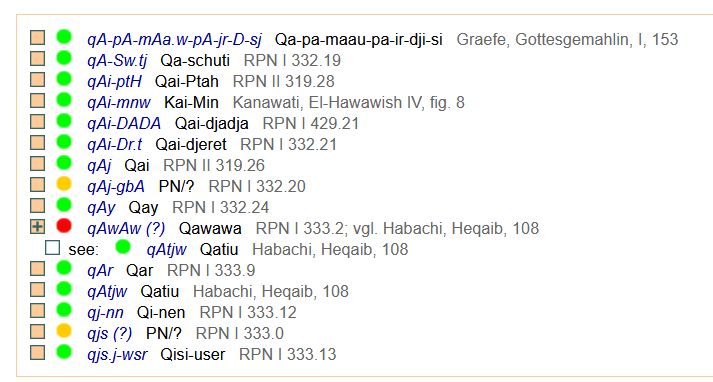

Finally, the concept of a hieroglyphic writing is also to be criticized. It suggests that there is some kind of standard writing for a lemma. This is, of course, completely absurd. No one who studies Egyptian texts and knows the variety of ways a word can be written will want to uphold this concept. Normally, different writings are noted for a lemma, such is the case in the Wörterbuch, in Lesko, A Dictionary of Late Egyptian or in Wilson, A Ptolemaic Lexicon. There are implementations for this in the digital domain as well. The AED offers for a lemma all writings sorted by frequency.  The new TLA unfortunately does not exploit its corpus for lexicographic purposes and does not determine the writings of a lemma on the basis of the occurrences. Too bad! Instead, the new TLA propagates this wrong conception of a standard writing. One can very well understand the development of how this came about. In the old TLA there is the possibility to search for hieroglyphics. Unfortunately, the basis of the search is not the writings from the corpus, but selected writings that are statically attached to a lemma. Users can add further writings on their own. However, this feature is apparently buggy and does not work properly. That is: the static writings serve a search. The new TLA now does not provide a hieroglyphic search. This removes the real purpose of these writings. Nevertheless, the static hieroglyphic writings are expanded in the lemmas. The above example https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/865595 is an entry that does not yet exist in the old TLA. Nevertheless, a hieroglyphic writing is given here. Especially the personal names have been enriched with hieroglyphic writings. This can be seen clearly in the comparison of the personal names starting with q:

The new TLA unfortunately does not exploit its corpus for lexicographic purposes and does not determine the writings of a lemma on the basis of the occurrences. Too bad! Instead, the new TLA propagates this wrong conception of a standard writing. One can very well understand the development of how this came about. In the old TLA there is the possibility to search for hieroglyphics. Unfortunately, the basis of the search is not the writings from the corpus, but selected writings that are statically attached to a lemma. Users can add further writings on their own. However, this feature is apparently buggy and does not work properly. That is: the static writings serve a search. The new TLA now does not provide a hieroglyphic search. This removes the real purpose of these writings. Nevertheless, the static hieroglyphic writings are expanded in the lemmas. The above example https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/865595 is an entry that does not yet exist in the old TLA. Nevertheless, a hieroglyphic writing is given here. Especially the personal names have been enriched with hieroglyphic writings. This can be seen clearly in the comparison of the personal names starting with q:

For the enrichment, however, the data from the corpus have not been used. Thus, the PN Qꜣ-Nj.t https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/713892 now has the writing 𓌖𓈎. The corpus provides exactly one instance of evidence https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/sentence/ICAAFUnlx753akI3hhllQVUmDX4 for this name. There the name is spelled 𓌖𓈎𓁐. Why not use this specific writing and not a writing which one cannot check? This is not scientific! Compared to the old TLA, quite a few hieroglyphic writings have been added to the lemma list, the origin of which cannot be checked, although there is no more hieroglyphic search at all and although the concept of a standard writing is not applicable for Egyptian. This is a blatant misconception.

For the enrichment, however, the data from the corpus have not been used. Thus, the PN Qꜣ-Nj.t https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/713892 now has the writing 𓌖𓈎. The corpus provides exactly one instance of evidence https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/sentence/ICAAFUnlx753akI3hhllQVUmDX4 for this name. There the name is spelled 𓌖𓈎𓁐. Why not use this specific writing and not a writing which one cannot check? This is not scientific! Compared to the old TLA, quite a few hieroglyphic writings have been added to the lemma list, the origin of which cannot be checked, although there is no more hieroglyphic search at all and although the concept of a standard writing is not applicable for Egyptian. This is a blatant misconception.

Redaction status

The same field also contains the redaction status. This takes the same form as in the hit list, i.e. there are three variants: verified, verification pending and inactive.

Persistent URL

Then the ID and the persistent URL are specified. With the help of three buttons you can copy the ID, the URL and the citation. More about this below!

Lemma list

Now the specification from which of the two lemma lists hieroglyphic/hieratic or demotic the entry originates.

Word class

In the next field, the word class is specified. Here it is word class as in the hit list and not part of speech as on the search page.

Translation

This is followed by the information that is the most important for most users, namely the translation of the word, in German, English and French.

Nominalbildung

Next, an innovation is provided that was not yet present in the old TLA. If the word in question is listed in the nominal formation classes according to Osing or Schenkel, this class is noted here. Unfortunately, it is not possible to search for this information.

Occurrences

Here is a button that leads to the occurrences. Here, as in the hit list, the attestation time is also indicated. For the detailed criticism of this concept see above.

Bibliography

The following is a bibliography. The abbreviations used are broken down in a separate page https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/listings/bibliography Unfortunately, this page is not always correct in alphabetical sorting. Furthermore, quite a few titles are missing there, e.g.

| bibliographical entry | occurs in: |

|---|---|

| Birk, Türöffner | in: wn-ꜥꜣ.wj-n-p.t https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/884213 |

| Engel, Private Rollsiegel | in: sꜣḏ.j https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/884741 |

| Gabler, in: Decoding Signs of Identity | in: Pꜣ-ds https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/885575 |

| Shorter, Catalogue | in: ḥz.yt-ꜥꜣ.t https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/884282 |

The abbreviations in this table are linked to the excellent (and freely accessible!) literature database Aegyptiaca. All these examples are from entries of this year. Apparently the abbreviation list is out of date and has not been updated. Apparently in the new TLA the project management does not work as well as in the old one, because there the abbreviation list does not have such gaps.

External references

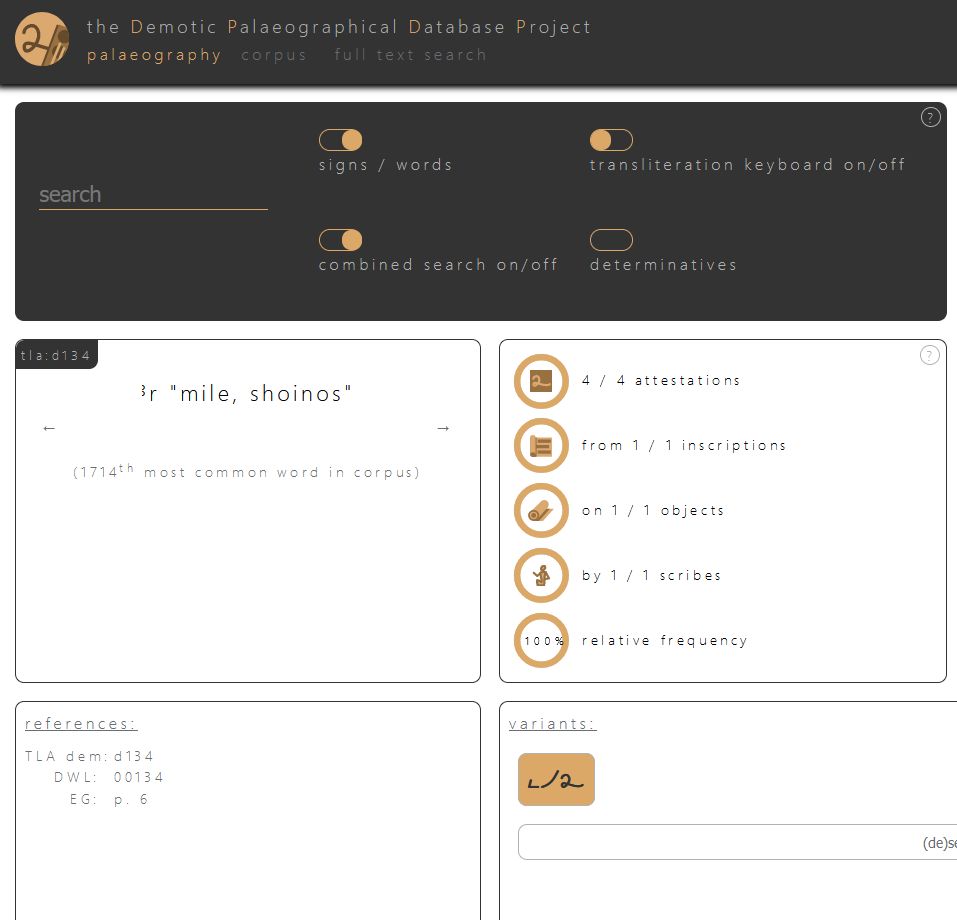

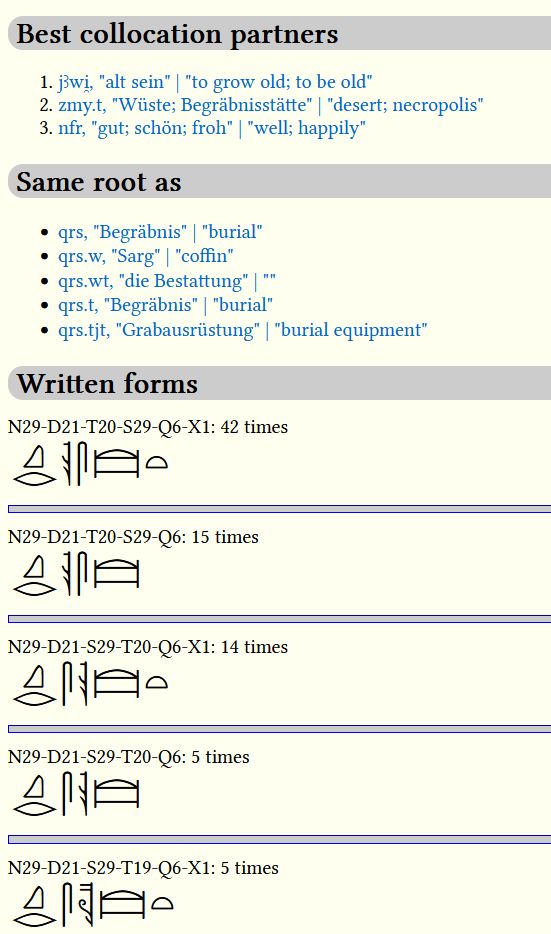

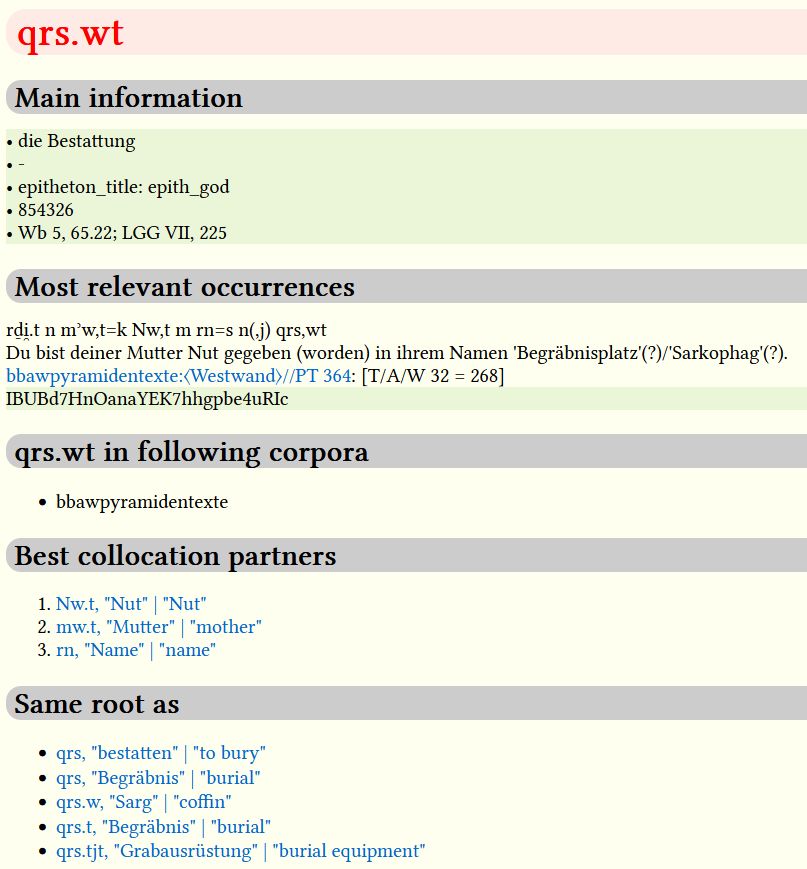

The External references item links to other digital projects that have more information about the entry. This is an excellent thing that the new TLA now links to other resources in more detail. The old TLA already provided the link to the Demotische Wortliste. This is also the case in the new TLA. There is now additionally the link to the old TLA, which funnily enough is called legacy TLA. One has a direct link into the DZA, the Digitized Slip Archive. For the Vocabulaire de l’Égyptien Ancien there is only the indication of the ID, but no link. This is perhaps because this project does not allow free access to its data, but is a paid product. Finally, there is a link to Projet Karnak. It is somewhat strange that two very important digital projects on Egyptian lexicography are missing, namely DPDP and AED. DPDP provides manifold paleographic information on very many demotic lemmas. DPDP even links into the new TLA, cf. e.g. http://129.206.5.162/beta/palaeography/palaeography.html?q=tla:d134.  A link back to DPDP would be very nice. It is incomprehensible that there is no link to AED. After all, lexicographic information - bundled from corpus data - is available there: Overviews of collocation partners, of writings of a word, of geographical and of chronological distribution. Here as an example qrs, to bury

A link back to DPDP would be very nice. It is incomprehensible that there is no link to AED. After all, lexicographic information - bundled from corpus data - is available there: Overviews of collocation partners, of writings of a word, of geographical and of chronological distribution. Here as an example qrs, to bury

This is all information that cannot be found in the new TLA in this way, but from which all Egyptological users would benefit. It is a testament to poor project management that time was invested in the following item instead of the fruitful link to DPDP and AED.

This is all information that cannot be found in the new TLA in this way, but from which all Egyptological users would benefit. It is a testament to poor project management that time was invested in the following item instead of the fruitful link to DPDP and AED.

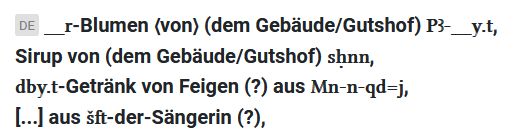

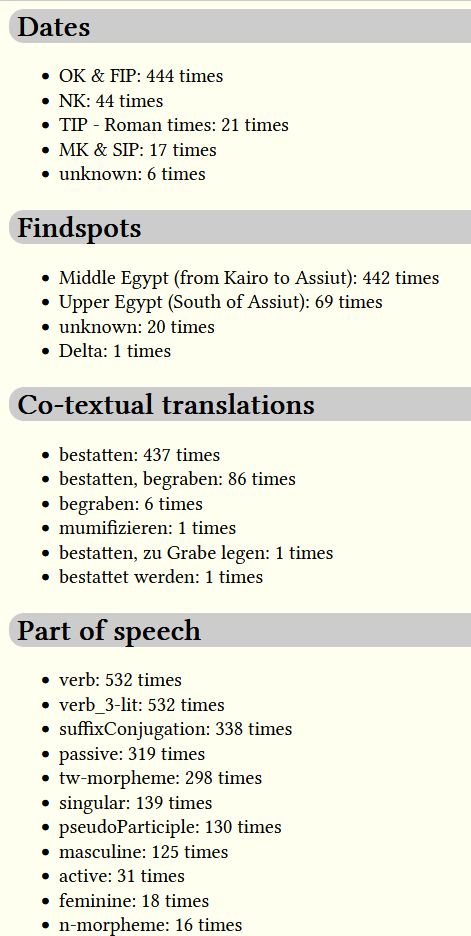

Comment

This is followed by a comment field, some of which offers so much text that there is a Show Comment button to display the entire content. The content itself is unstructured text. Unstructured in the sense that it does not contain hyperlinks, for example, when referring to other commentaries, as in https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/872159, or even partial headings, which would be desirable given the length. The commentaries are a presentation of opinions on a lemma as found in the literature. This also involves going deep into the 19th century, cf. https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/45. Mostly it remains a mere listing of opinions without drawing any conclusion. The reader is left perplexed when he reads, for example, the comment in https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/854631.  Is now to read mꜣš.t as the entry is set in the TLA, or mš.t as it is at the beginning of the paragraph in the comment? Is the referenced identification of the duck that Boessneck makes now the prevailing view? How is it to be evaluated? This is simply pouring out a box of notes without coming to a conclusive conclusion. Also, the detailed history of research from the above example https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/45 obscures the information to determine meaning. Does the information from the 19th century help if one wants to know what ꜣw.t-jb means?

Is now to read mꜣš.t as the entry is set in the TLA, or mš.t as it is at the beginning of the paragraph in the comment? Is the referenced identification of the duck that Boessneck makes now the prevailing view? How is it to be evaluated? This is simply pouring out a box of notes without coming to a conclusive conclusion. Also, the detailed history of research from the above example https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/45 obscures the information to determine meaning. Does the information from the 19th century help if one wants to know what ꜣw.t-jb means?

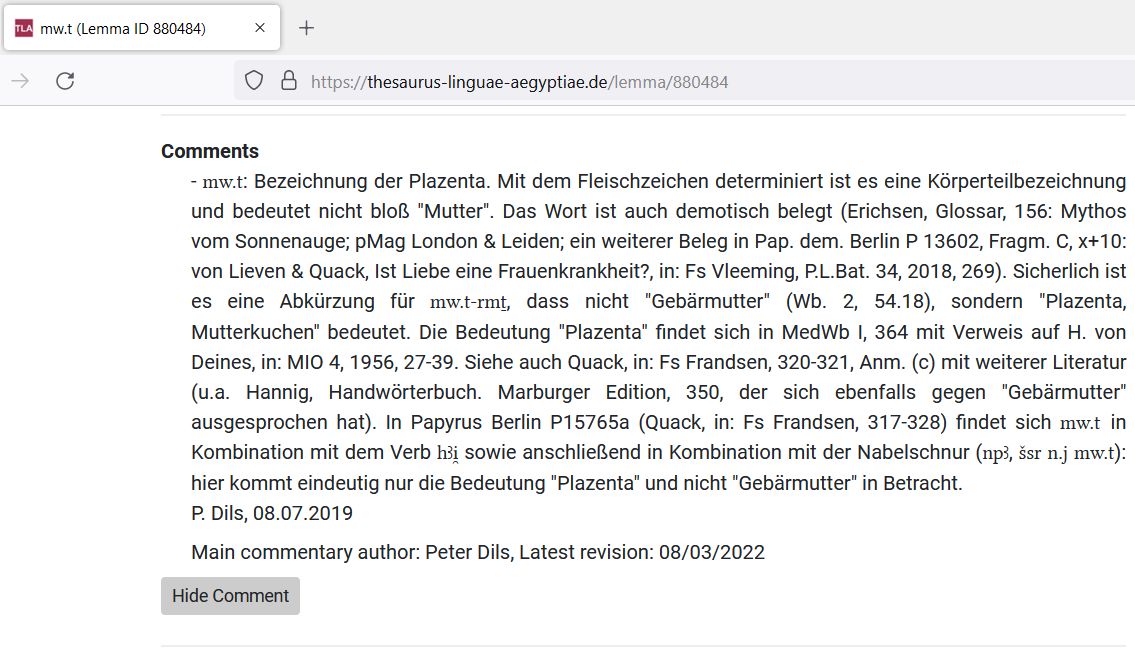

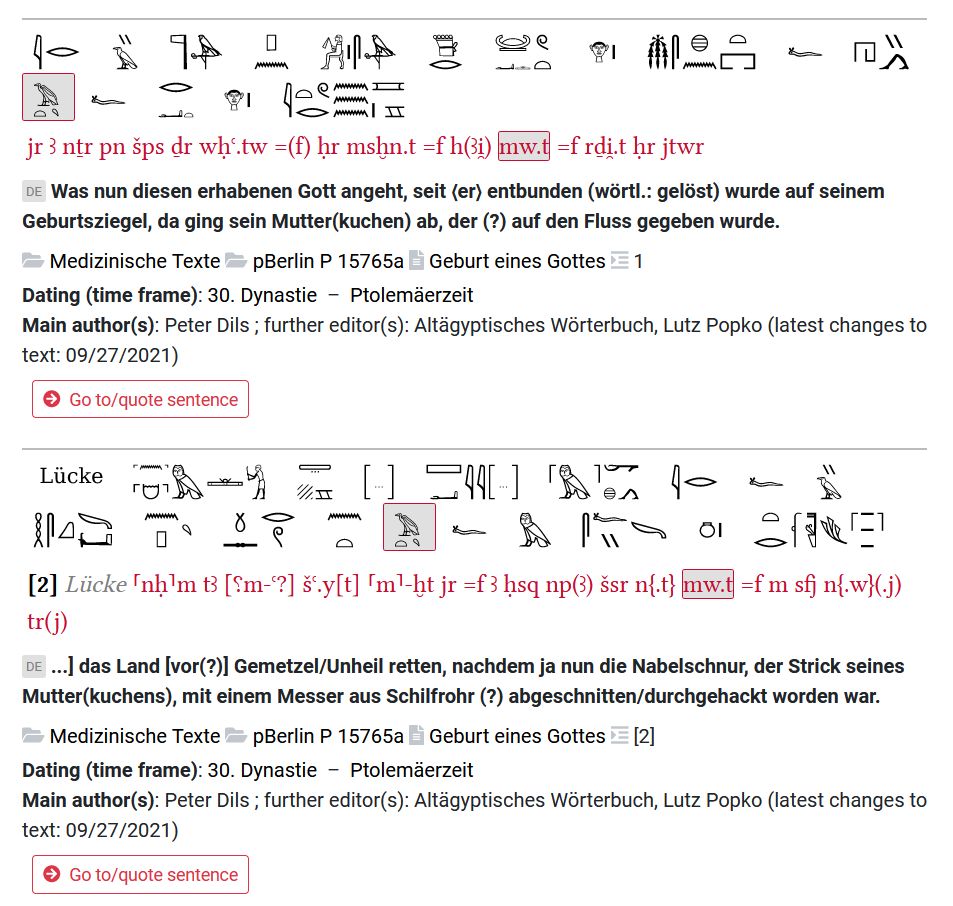

The commentaries appear within the new TLA as a foreign body that is not properly integrated. For example, Peter Dils writes in his comment for the Egyptian word for placenta https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/880484: “Bezeichnung der Plazenta”, while he translates, however, in the two occurrences of the word “Mutter(kuchen)”.

The comment to https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/132250 mentions another plant name and references the Wörterbuch, but does not give the ID of the lemma from the TLA https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/132240!

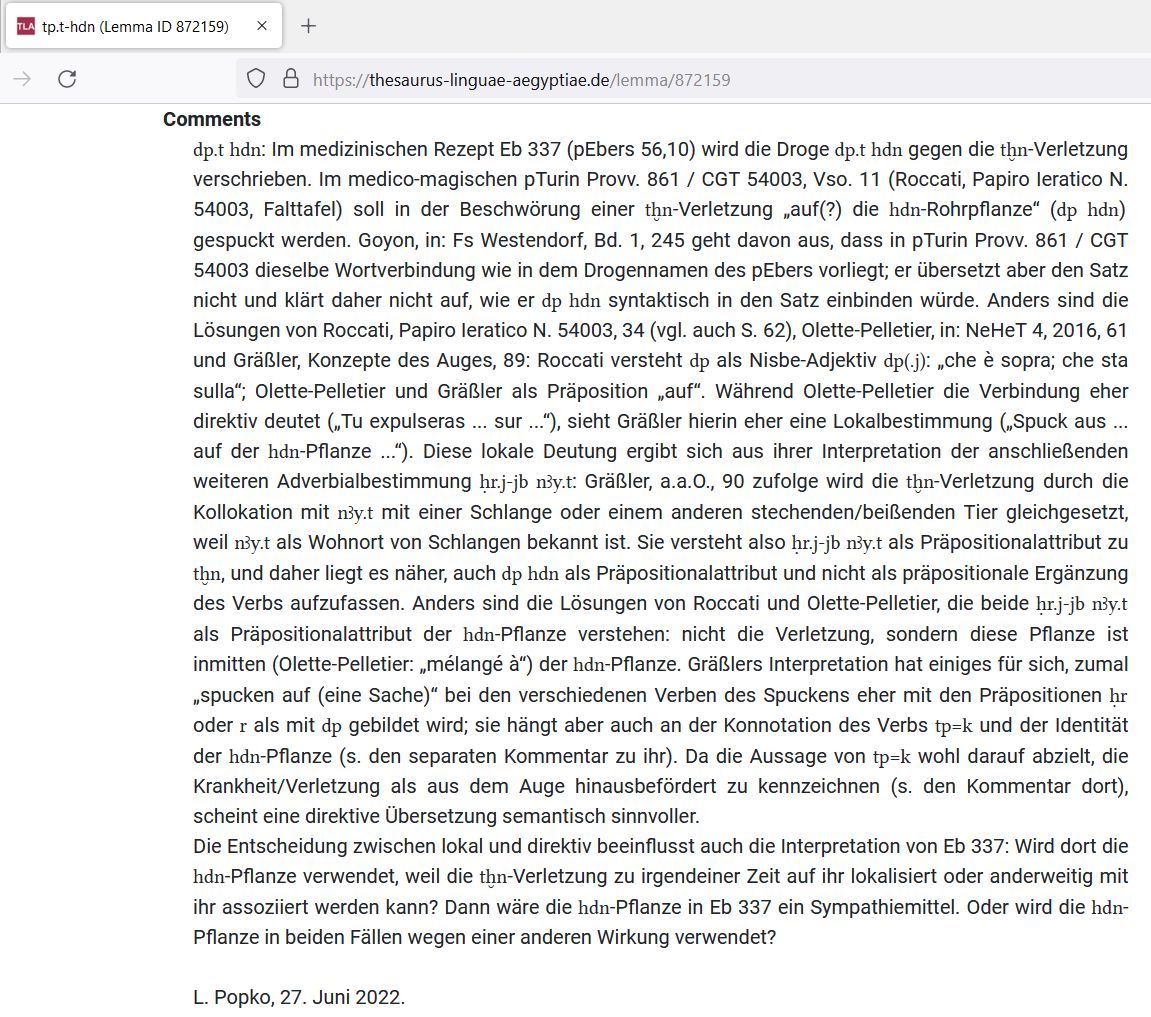

Also, the interaction between the actual lemma entry and the comment does not work. https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/872159 is set as tp.t-hdn, while Lutz Popko writes dp.t-hdn in his comment. Who reads after the convincing paper by Roberson, Tête-à-tête. Some Observations and Counter-Arguments Regarding a Contentious Phonological Value, dp or tp. In: LingAeg 26, 2018, 185-202, still dp instead of tp?

This coexistence of the actual lemma entry and the comments is explained by the fact that completely different persons are responsible in each case: However, the authors of the comments, which are mainly Peter Dils and Lutz Popko and occasionally Anke Blöbaum, are not authors of the lemma entries: They are not responsible for the entries they comment on, nor for any others. According to https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/info/lemma-lists the responsibility lies with Ingelore Hafemann and Simon Schweitzer, who belong to the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, while the mentioned authors of the lemma comments are employed at the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Leipzig. So here the project management has failed, so that now there is no unified result.

The content of some of the comments is also of inferior quality. The commentary on the epithet wꜣḏ-n-Sḫm.t https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/853645 references Flessa, pVienna Aeg 8426, who claims that there is no pre-Ptolemaic evidence for wꜣḏ, “child; son.” This is not tenable, as the evidence in the new TLA shows. Why does Lutz Popko, who is himself responsible for a pre-Ptolemaic record, discuss this claim? Why doesn’t he set the record straight?

Janssen had proved that jdg https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/34270 is a kerchief. In the commentary this identification is now doubted unconvincingly. Lutz Popko points to the high price jdg can have if it is made of šmꜥ nfr. He rules out the possibility of servants wearing a kerchief, „aber sicherlich kein Tuch aus „gutem dünnen Leinen“ leisten konnten.“ But Janssen, Prices, 284, writes:

The prices for the kerchief vary considerably, and this may be due not only to differences in quality, but to the varying length of the pieces of cloth, about which nothing is known. The average price appears to be 10 to 15 deben for an ꞽdg of thin cloth, and if this is correct, no. 1 is clearly cheap, since the quality is šmꜥ nfr

This removes Popko’s main objection.

The comment to https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/20650 excludes Hannig’s translation suggestion, namely “Schlinge”, because of the determinative. This is too hasty and methodically unclean, if the scripture is made absolute. Then Lutz Popko would also have to reject that the ꜥpšꜣ.yt-animal is a beetle because it can be written with 𓄛.

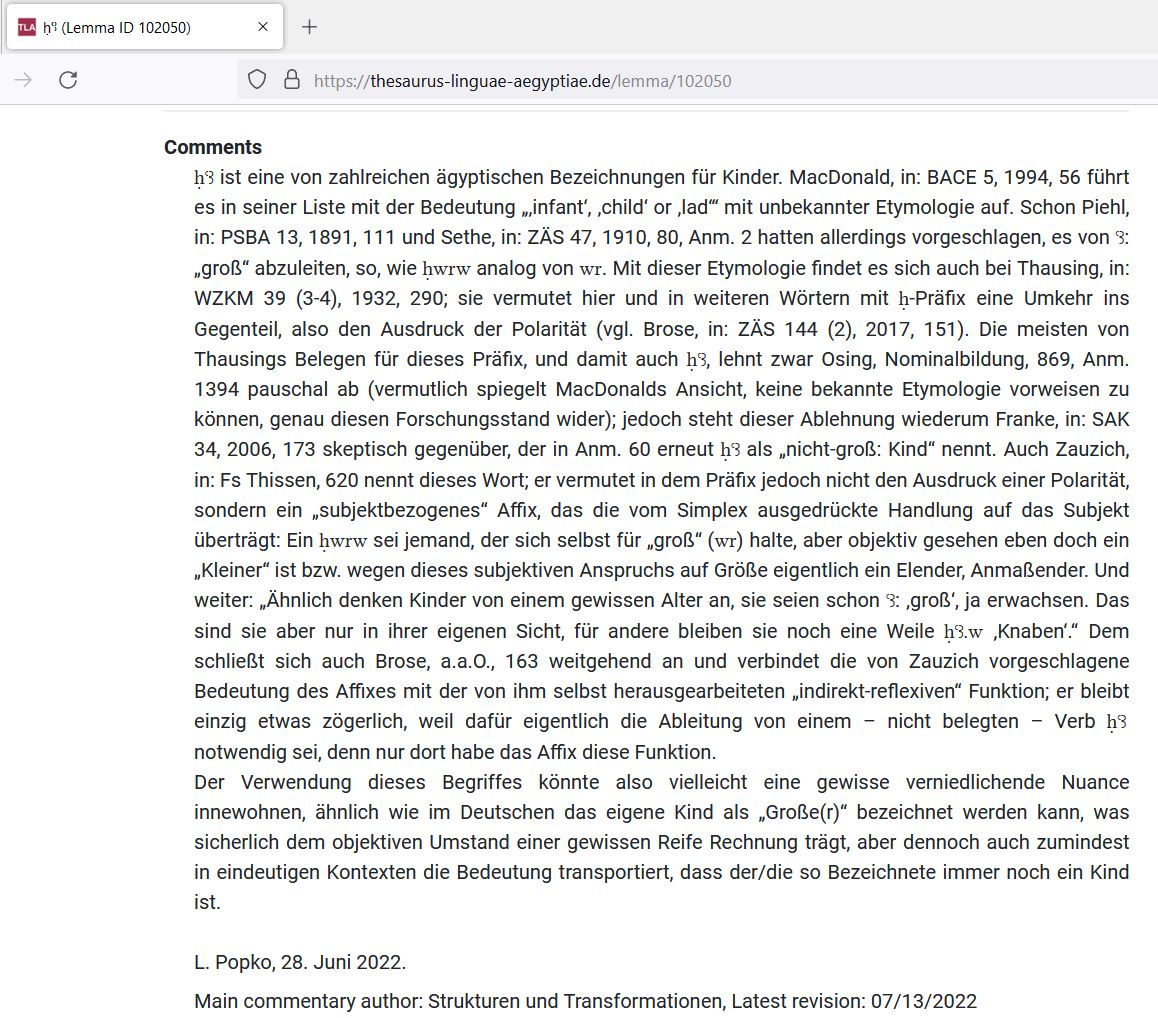

The comment to https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/102050 seriously discusses whether there could be an ḥ-prefix in the word ḥꜥꜣ. With this guessing one leaves the secure ground of Egyptian word research.

We leave it with these four examples. Dimitri Meeks would write a lengthy article that would not be pleasant for the comment authors to read. Why does the project afford itself the luxury of producing lexicographic results at both sites, in Berlin and in Leipzig? Why does it not stick to the one location Berlin, where the lexicographic competence is available? Why does Leipzig not reflect on its strengths in corpus building? In any case, this organization of work does not bear fruit!

Author

The next unit contains four items of information, that of the main author, that of the further editors, the time of the last change and the redaction status. It is not clear why the redaction status is mentioned again here. Also the difference between main author and further editors is not clear. Did the further editors only take over editorial tasks? Who is the author of the entry? The main author alone? But then why is he called main author and not just author? This is very confusing and inconvenient when you want to cite the entry. Also the sorting of the further editors is not obvious. In https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/855167 it says “Emilia Mammola, Simon D. Schweitzer”, but in https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/713892 it says “Simon D. Schweitzer, Emilia Mammola”. Is the order due to the number or relevance of the changes? “Altägyptisches Wörterbuch” and “Simon D. Schweitzer” act as the main author. If we look at it correctly, the entries that already exist in the old TLA have “Altägyptisches Wörterbuch” as main author. For the new entries “Simon D. Schweitzer” is responsible. This is the Egyptologist who also published the AED. In this respect, lexicographic competence is at work in the new TLA. The time of the last change is given in the format MM/DD/YYYY. Why is ISO 8601, the usual YYYY-MM-DD, not used?

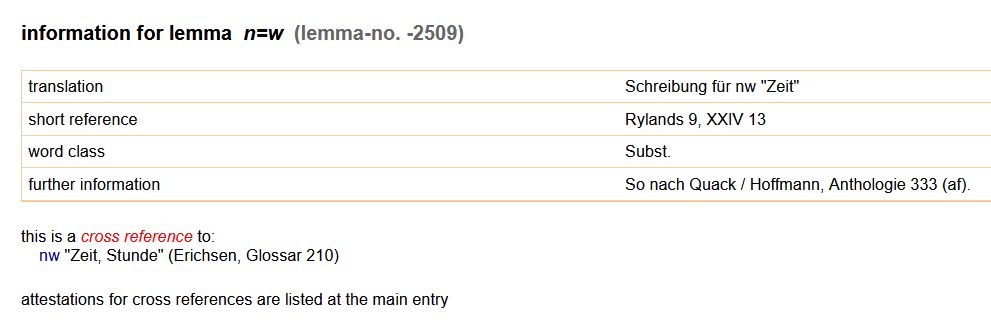

Relations

The next unit of information is a cream puff. Many thanks for that! If you want to create a network of Egyptian lemmas, you will find the corresponding relations here. This section is, in our opinion, the most successful on the whole lemma details page. In the old TLA there are three types of relations that lemmas can enter: the cross reference, the hierarchical relation and relation of composition. In cross reference, an obsolete lemma is linked to a regular lemma.  The hierarchical relation links an upper lemma with its sublemmas. Both relations are already visible in the hit list. More about this above! The relation of composition links a compound with its components. In the old TLA this information is only available on the lemma details page.

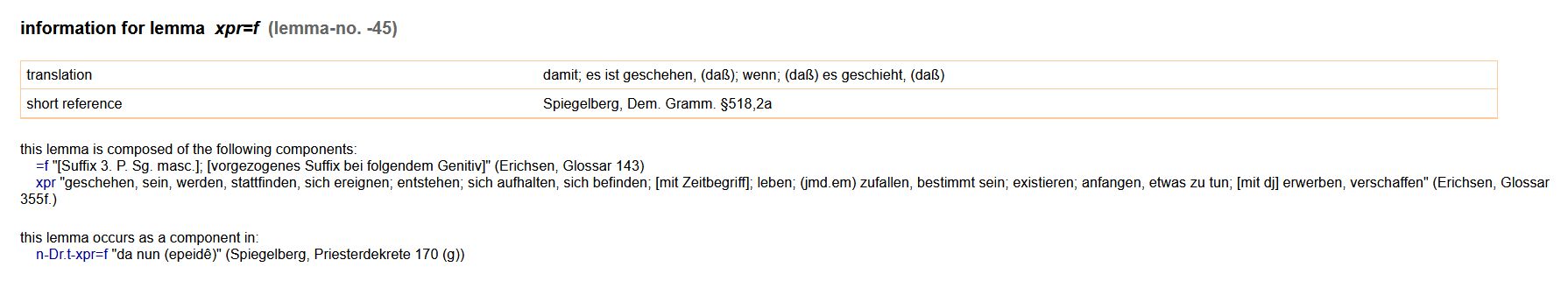

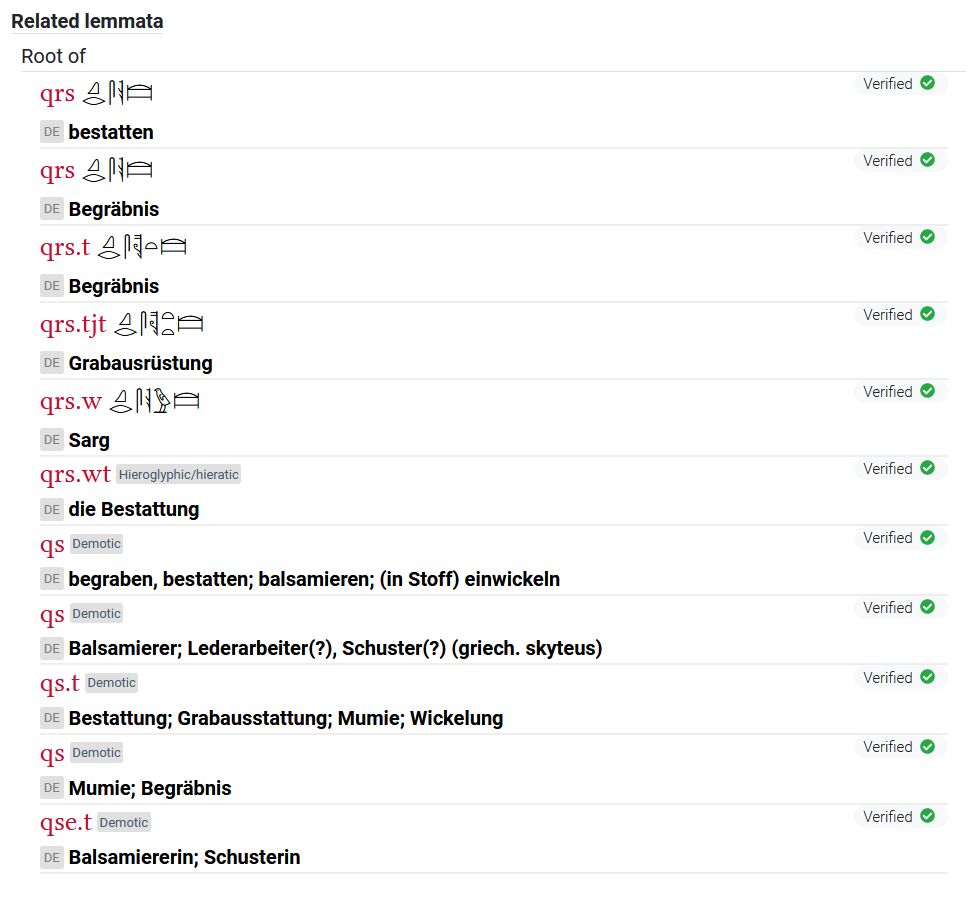

The hierarchical relation links an upper lemma with its sublemmas. Both relations are already visible in the hit list. More about this above! The relation of composition links a compound with its components. In the old TLA this information is only available on the lemma details page.  These three types of relations are also available in the new TLA, but unfortunately - as noted above - not in the hit list, but in the lemma details page. New are the two relations: root and chronological relation. With root, a connection is made between the root and all lemmas that are derived from this root. This is implemented differently than in the AED. There, for a lemma, it is listed which other lemmas exist that belong to the same root.

These three types of relations are also available in the new TLA, but unfortunately - as noted above - not in the hit list, but in the lemma details page. New are the two relations: root and chronological relation. With root, a connection is made between the root and all lemmas that are derived from this root. This is implemented differently than in the AED. There, for a lemma, it is listed which other lemmas exist that belong to the same root.  In the new TLA you have the link between root and lemma. So if you want to find the other lemmas that belong to the same root, you have to go to the root entry.

In the new TLA you have the link between root and lemma. So if you want to find the other lemmas that belong to the same root, you have to go to the root entry.  The chronological relation links a demotic lemma with its pre-demotic predecessor. This procedure is already known from DPDP, where an entry is linked to both its pre-demotic predecessor and its Coptic successor.

The chronological relation links a demotic lemma with its pre-demotic predecessor. This procedure is already known from DPDP, where an entry is linked to both its pre-demotic predecessor and its Coptic successor.  Why does the new TLA not link the Coptic successor? The Coptic word list on which the Coptic Dictionary Online is based was compiled at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, which is also the home of the TLA. Why not join forces on one project? This is a wasted opportunity of the new TLA. Could the Coptic have been included in its concept? For the individual relation types, the lemmas are listed which are related according to this type. Unfortunately, a sorting is not available. It is generally to be noted that often the sorting is omitted in the new TLA. More about this below at the occurrences! Unfortunately, this is not user-friendly at all.

Why does the new TLA not link the Coptic successor? The Coptic word list on which the Coptic Dictionary Online is based was compiled at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, which is also the home of the TLA. Why not join forces on one project? This is a wasted opportunity of the new TLA. Could the Coptic have been included in its concept? For the individual relation types, the lemmas are listed which are related according to this type. Unfortunately, a sorting is not available. It is generally to be noted that often the sorting is omitted in the new TLA. More about this below at the occurrences! Unfortunately, this is not user-friendly at all.

Citation note

At the end of the entry there is a citation note that gives two recommendations on how to cite the web page, a detailed way and a concise way. To evaluate this properly, please imagine the following scenario: You want to publish an essay in a journal, so you send your paper to JEA. JEA accepts your paper, but places a citation notice under your paper and under all papers, stating how they would like to cite your paper or the paper in question. And this citation notice reads name of essay, in: The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 110, 2024, 11-34, ed. by Claudia Näser. This reference does not even say who the author of the paper is, but only the editor of the journal. That’s a very crazy way to cite an essay when the editor takes the place of the author, isn’t it? But that is exactly what happens with the citation reference in the new TLA. The actual author of the paper, i.e., the lemma entry, the text, the sentence, or the thesaurus entry, is not named; instead, the editors of the new TLA are there. This is not only absurd, but also violates the license under which the data of the new TLA is held. According to https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/info/licenses, the data is licensed under the CC-BY-SA 4.0 Int. license. This license requires author attribution, but this citation neglects to do so. Perhaps this is just ignorance, perhaps even arrogance. Most certainly, this is extremely embarrassing.