Collocations

We have expanded our web pages by offering not only the occurrences of all words, but also their collocations.

What is a collocation? The Cambridge Dictionary defines this term as follows:

a word or phrase that is often used with another word or phrase, in a way that sounds correct to people who have spoken the language all their lives, but might not be expected from the meaning

The (old) TLA also uses this term:

Within linguistics, the term collocation denotes the co-occurrence of two or more words on a regular basis. Collocations may be lexical (“New York”) or quasi-lexical (“at first go”) in status. In a broader sense, collocations reflect idiomatic expressions (e.g., “to kick the bucket”) or stereotyped expressions (e.g., “bitterly cold”).

The term has - if you will - two perspectives. One is easy to determine. The basic condition for a collocation is the co-occurrence of two words, as the two definitions suggest. This condition is necessary, but not sufficient. When, then, is a co-occurrence a collocation? This brings us to the second perspective, which is difficult to grasp. The Cambridge Dictionary says “often used”, the TLA speaks of “on a regular basis”. This is not to be fixed a priori, but rather spongy. If one wants to capture the boundary between collocation and no collocation, one has to do one’s own research on a larger data set. We draw the following conclusion: whether a co-occurrence is a collocation or not is not at the beginning of the research, but at the end. One must not rule out potential collocations from the outset. Thus, in order to study collocations in the Egyptian language, one must consider all co-occurrences! Therefore, we follow a very pragmatic approach: We list every co-occurrence as a collocation. (That is why we speak of “List of all collocations”. But we call the single attestations “cooccurrences”, because they are potentially a collocation).

But at what point is something considered a cooccurrence? Are the first and last words from Hamlet a cooccurrence? Again, we take a pragmatic approach. Anything within a sentence counts as a cooccurrence. Last word of one sentence and first word of the following sentence do not count as a cooccurrence.

Enough introductory words! Let’s take a look at an example that shows how we present Egyptian collocations. The collocations to Nṯr.j-msw.t, the nebty name of Senusret III, are collected in https://oraec.github.io/corpus/collocation_853576.html. The URL includes the prefix “collocation” followed by the ID of the lemma.

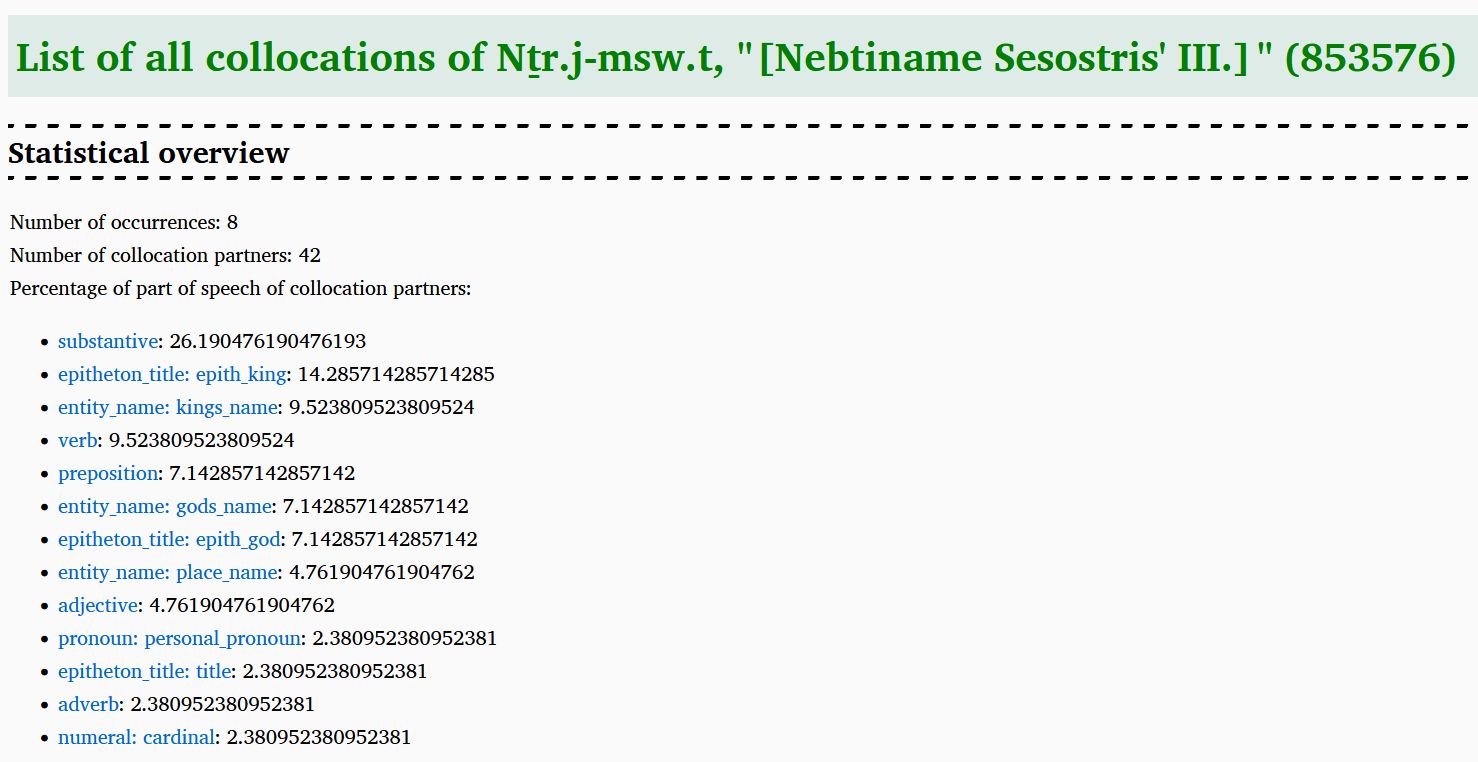

The web page consists of three sections: statistical overview, alphabetical overview, collocations sorted by frequency.

The statistical overview provides the number of occurrences and the number of collocation partners, i.e. words that occur together with the actual word. This gives an indication of how frequent the lemma is and how flexibly it chooses its collocation partners. If a word occurs primarily in fixed phrases, the number of collocation partners is small. These collocation partners are further broken down by their part of speech. This provides a first impression of the types of words it co-occurs with. Titles have a fairly high proportion of titles as collocation partners because they appear together in title sequences. As a comparison, here is a table that has as its basis all the lemmatized tokens in ORAEC:

| Part of Speech | Proportion in percent |

|---|---|

| substantive | 25.348550919049924 |

| verb | 16.05086449356941 |

| pronoun: personal_pronoun | 15.99489609260973 |

| preposition | 13.317398598992824 |

| adjective | 5.443440464897158 |

| particle | 3.633068082478938 |

| epitheton_title: title | 3.2148454899866628 |

| entity_name: gods_name | 3.003423571682556 |

| pronoun: demonstrative_pronoun | 2.9288418263670217 |

| numeral: cardinal | 2.585714450758718 |

| entity_name: person_name | 2.01704468871428 |

| entity_name: kings_name | 1.1988277444092574 |

| epitheton_title: epith_god | 1.106659597874741 |

| adverb | 1.0987007885639613 |

| entity_name: place_name | 0.8904880675625889 |

| entity_name: artifact_name | 0.38279305427009375 |

| pronoun: relative_pronoun | 0.3663619640800964 |

| undefined | 0.33619550943439824 |

| interjection | 0.32785159644729023 |

| epitheton_title: epith_king | 0.3064141584650281 |

| entity_name: org_name | 0.10012695584529616 |

| entity_name | 0.0985865411399839 |

| pronoun: interrogative_pronoun | 0.09730286221889037 |

| numeral: ordinal | 0.04621244115936745 |

| epitheton_title | 0.04248977228819619 |

| pronoun | 0.03440259508530688 |

| numeral | 0.02644378577452693 |

| entity_name: animal_name | 0.0014120468132028945 |

| root (obviously a data error) | 0.0006418394605467702 |

Thus, 25% of the lemmatized tokens are nouns, 16% are verbs. If the values on the collocation overview of a lemma deviate strongly from this table, one has a first indication of a significantly deviating use of the lemma (compared to all lemmas). The parts of speech are linked, by the way. For example, if you click on “adverb”, you will get all references for adverbs.

In the example - as in all lemmas - the noun is in the first position. In the second and third position, however, there are parts of speech that belong to a royal speech act. This is not surprising. The nebty name is, of course, in the titulary next to other royal names and next to the royal titles.

In the example - as in all lemmas - the noun is in the first position. In the second and third position, however, there are parts of speech that belong to a royal speech act. This is not surprising. The nebty name is, of course, in the titulary next to other royal names and next to the royal titles.

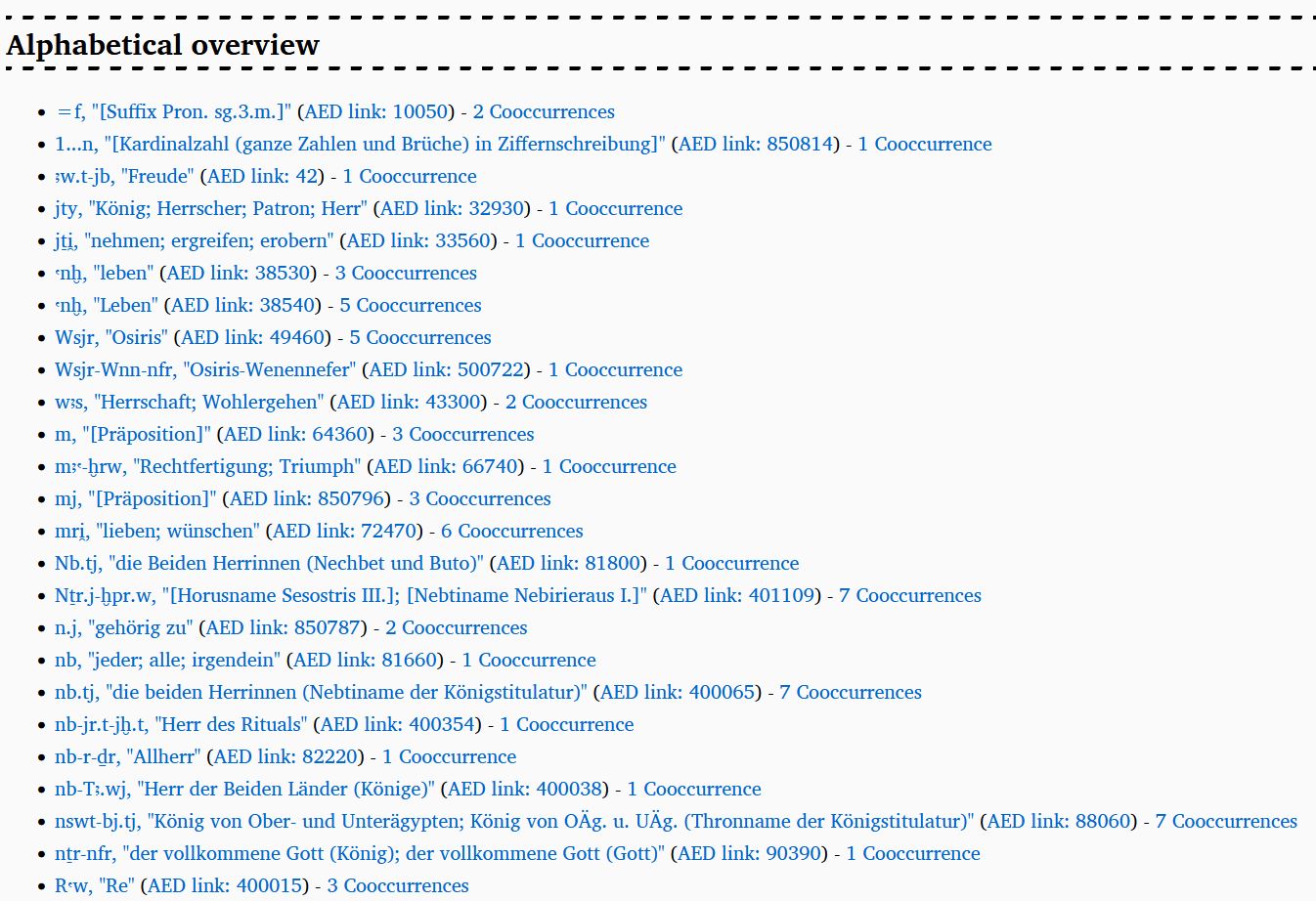

The alphabetical overview lists all collocation partners. A line with a collocation partner contains three links: to the collocation partner’s occurrences, to the collocation partner’s entry in AED, and to the attestations of this collocation. Thus, if one is looking specifically for the collocation of two lemmas, one can first go to the collocations page of the first lemma and then look for the other lemma in the alphabetical overview.

The alphabetical overview lists all collocation partners. A line with a collocation partner contains three links: to the collocation partner’s occurrences, to the collocation partner’s entry in AED, and to the attestations of this collocation. Thus, if one is looking specifically for the collocation of two lemmas, one can first go to the collocations page of the first lemma and then look for the other lemma in the alphabetical overview.

Finally, all collocations - sorted by the collocation partners - are listed. First are the collocations of the collocation partner that has the most collocations with the actual lemma. If you click on a collocation, you get to the sentence view in which the collocation is used. If you look at the most frequent collocation partners, you get a good impression in which context the lemma is used. In our example, we see other royal names and elements of the titulary.

Finally, all collocations - sorted by the collocation partners - are listed. First are the collocations of the collocation partner that has the most collocations with the actual lemma. If you click on a collocation, you get to the sentence view in which the collocation is used. If you look at the most frequent collocation partners, you get a good impression in which context the lemma is used. In our example, we see other royal names and elements of the titulary.

What is the use of these collocations? From a philological point of view, the answer is quite simple: If you know the collocation partners, you can better fill in gaps in the text. But we have hinted at something else in this blog. The collocation partners teach us the usage of a lemma. Thus, collocations are not only useful for philology, but also for lexical semantics. We encourage all students looking for a thesis to look at these collocations and explore them with digital tools. This is a very fruitful area! Take advantage of it! We plan to make the collocations available in other ways (perhaps as a network) soon. Stay tuned!

This work is marked with CC0 1.0 Universal