Type token ratio

Continuing with the filling of our statistics pages! Last time we counted the hieroglyphs of a text, listed the most frequent hieroglyphs and described the inequality of the distribution. This time we are not talking about hieroglyphs, but about words.

We have again packed our results into a JSON and attached it to the respective statistics page. For each text, we counted how long the text is, that is, how many word forms it consists of. This information is in the tokens field of the JSON file. Furthermore, we counted how many different words the text consists of. This is the value of the types field. What is the difference? Suppose nṯr, the Egyptian word for “god”, is used ten times in a text. Then that’s 10 tokens each with one word form nṯr or nṯr.w or whatever, but it’s only one type because all ten word forms represent the same one word nṯr. O.k.? This means that the number of types is always less than or equal to the number of tokens.

In “frequency” you can see how often which word is used in a text. The list there is sorted by frequency. At the beginning is the most frequent word, at the end of the list the words appear that are used only once.

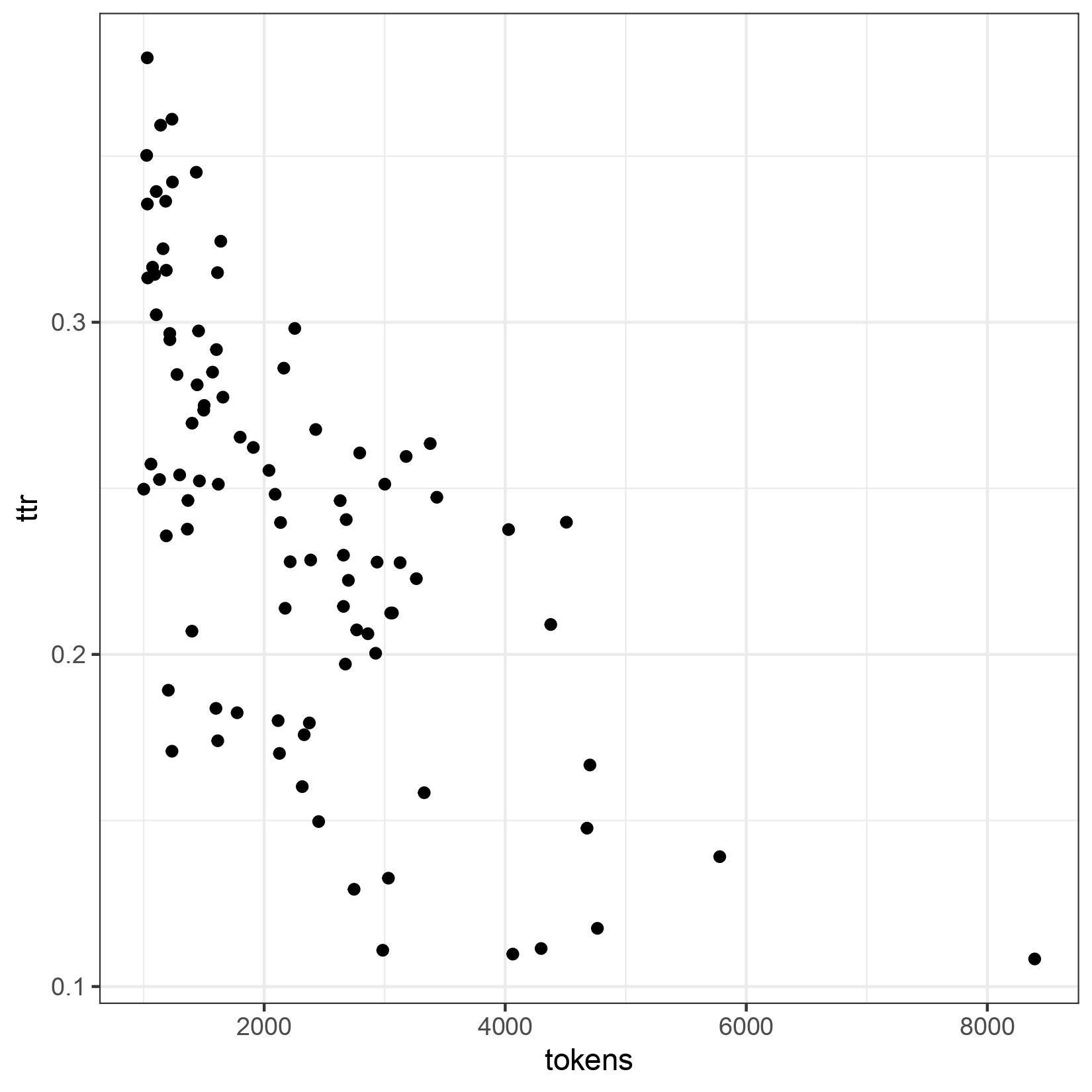

These numbers are nice, but what use do they have? Well, they can be used to describe and determine the lexical richness of a text. Everyone will agree that a text written by an elementary school student has nowhere near the wealth of vocabulary as a work of high literary standing like Ulysses. James Joyce used more types in his work than an elementary school student does. The types and tokens thus give an indication of the lexical richness of a text. Most prominent now is the so-called type token ratio (ttr), which is simply the quotient of types and tokens, i.e., it can take values between 0 and 1. The big advantage is that it can be calculated very easily. The disadvantage is that it is strongly dependent on the text length. This is easy to explain. The longer a text becomes, the more likely it is that words will be reused. Inevitably, ttr becomes smaller the longer the text is. This assumption can be confirmed with the ORAEC data:

We have evaluated texts that are longer than 1000 tokens. On the x-axis is the number of tokens, on the y-axis the ttr. You can clearly see that as the text length increases, the ttr gets smaller. A ttr, as prominent as it is, can only be a first start, and should only be used in cases where the text length is approximately the same.

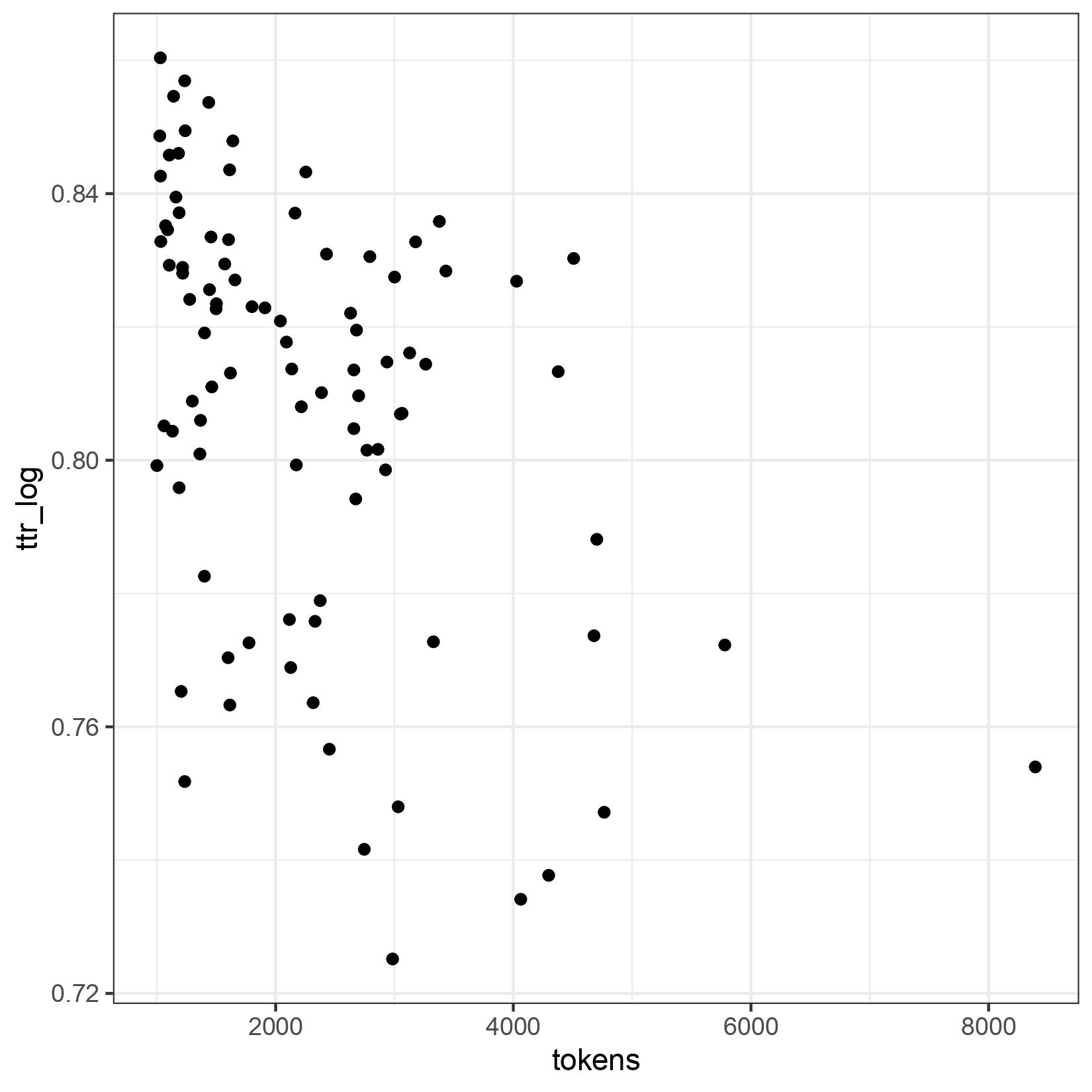

To mitigate the influence of the text length, there are various modifications of the ttr. In addition to the ttr, we also calculated the bilogarithmic ttr by first calculating the logarithm to base 2 for types and tokens, respectively, and then determining the quotient from this. We chose exactly this modification because the (good old) TLA lists it on its statistics pages. But the ORAEC data show that there is also a dependency on the text length:

The fluctuations are no longer as large as with the simple ttr, but the influence of the text length is still visible. Here, too, the value decreases as the text length increases.

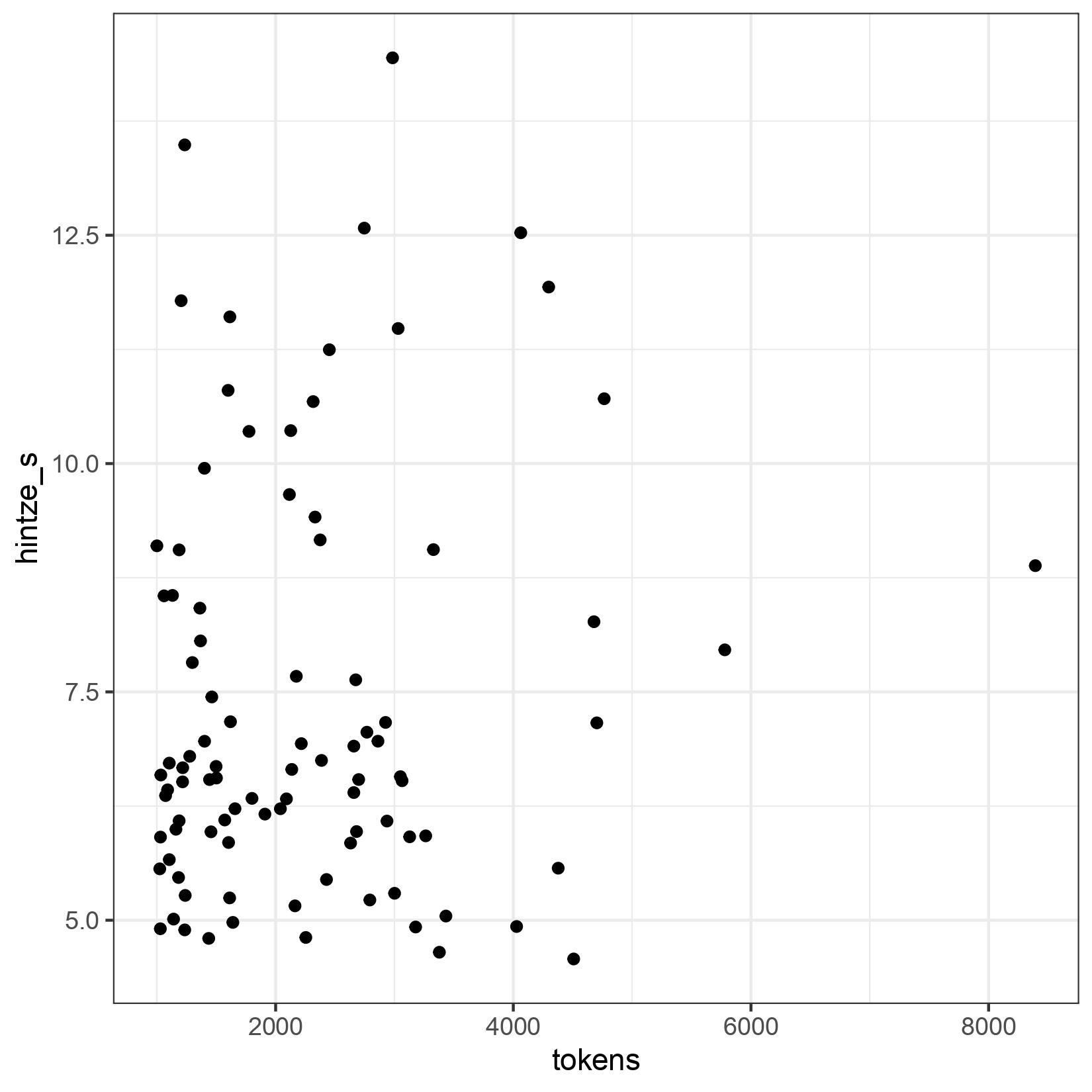

In Egyptology, a ttr dependent on text length does not play a major role. Some attention, however, has been paid to a paper by Hintze (Hintze, Fritz: Die statistische Struktur des Wortschatzes ägyptischer Literaturwerke. I. Der Reichtum des Vokabulars. In: ZÄS 102, 1975, 100-122), soon to be fifty years old, which proposed another measure of lexical richness. S* is defined as follows:

\[S^{\*} = {\overline{f} - D^{\*} \over \sqrt{N}}\]In this context: $N$ is the number of tokens, $V$ the number of types, $V_i$ the number of types with frequency $i$ and further:

\[\overline{f} = {N \over V}\] \[D^{*} = { {4V_1 - V_2} \over {4V_1 - 2V_2} }\]The smaller S* is, the greater the lexical richness of a text.

As the ORAEC data show, this is finally a measure that does not depend on the text length.

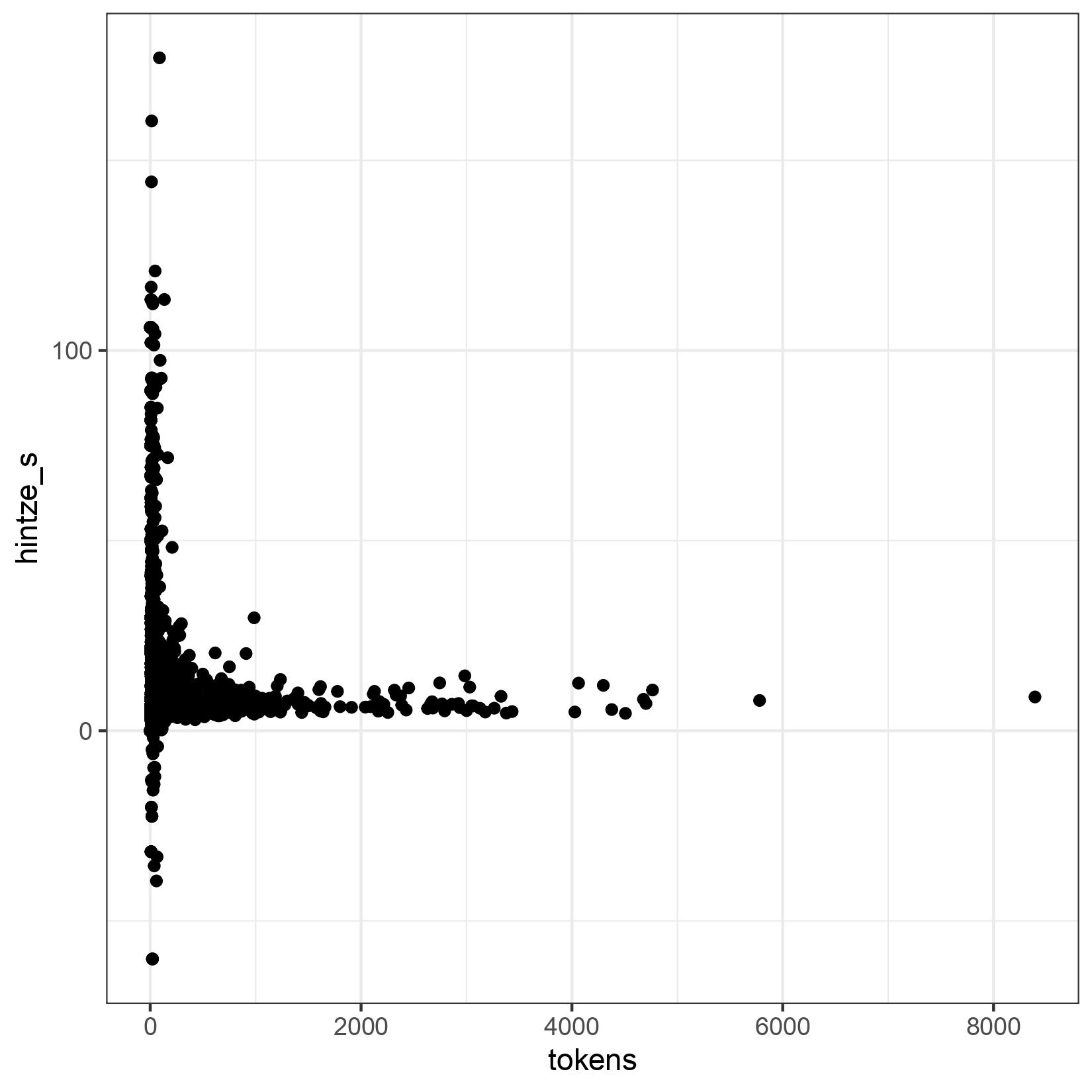

Again, we have evaluated texts starting at 1000 tokens. Because if you consider all texts, even the very short ones, the values scatter a lot. Here is the graph:

But here, too, one can clearly see that the text length has no influence on S*.

Several Egyptologists have used this index S* to measure the lexical richness of a text. Lepper, 258 (Lepper, Verena: Untersuchungen zu pWestcar. Eine philosophische und literaturwissenschaftliche (Neu-) Analyse. 2008) summarizes the results clearly in a table listing the texts counted so far with their S* values. We provide a selection in a table here:

| Text | Hintze’s S* |

|---|---|

| Wenamun | 10.942 |

| Westcar | 9.65095 |

| Piye | 6.038 |

| Lebensmüder | 5.824 |

| Sinuhe | 5.044 |

| Merikare | 4.964 |

| Amenemhet | 4.176 |

The texts listed here have also been calculated by us:

| Text | Hintze’s S* |

|---|---|

| Wenamun | 11.479168603755491 |

| Westcar | 9.058201954064678 |

| Piye | 5.569958028531067 |

| Lebensmüder | 6.669820102587212 |

| Sinuhe B | 4.925963295766788 |

| Merikare | 5.157697064157509 |

| Amenemhet | 4.53635949072746 |

The fact that the numbers do not agree perfectly is due to the norm of data collection, e.g. whether a suffix is counted as an independent type or not. The changes are significant in that, depending on the norm, Piye or Lebensmüde has a greater richness. One cannot avoid calculating the variance to the value, so that one can evaluate to what extent differences of two S* values are significant. But this is beyond our ambition. Rather, we wanted to provide the first steps for an assessment of lexical richness. An in-depth assessment still needs further indices (cf. e.g. https://quanteda.io/reference/textstat_lexdiv.html) and also the investigation of subvocabularies, which Hintze has already partly done. People, get going!