Guest post: Early Egyptian inscriptions matter or why is the phonetic value of 𓍋 mr

A slightly different blog this time. We’re going to give the floor to Drea, our expert of the Early Dynastic Period. Please, Drea, go ahead!

Hello dear readers! My name is Drea Fante and I’m a big fan of Early Dynastic Egypt because it’s just so exciting to watch Egyptian culture develop. You get to see it grow. The inscriptions are very appealing to me. So I’m very happy that there are so many tools available to study them:

Important tools for the study of early inscriptions

Each inscription has its own ID that you can quote. The numbering system inspired us to introduce the ORAEC numbers. The inventor of the IDs of the Early Dynastic inscriptions is Jochem Kahl, who used them to organize the Early Dynastic inscriptions as a “source list” for his dissertation by sorting the inscriptions chronologically and assigning them a sequential number. Ilona Regulski has integrated and continued the system in her database of Early Dynastic inscriptions. Finally, Gunnar Sperveslage has presented a monograph which adopts the numbering system of Kahl and Regulski and introduces new IDs for other, additional inscriptions. Jochem Kahl writes about the “source list” in his dissertation on page 13 in footnote 17:

In der Hoffnung, daß dieser Anhang auch für zukünftige Forschungen auf dem Gebiet der 0.-3. Dynastie eine Grundlage bilden kann.

So this hope has been fully confirmed!

What is this dissertation mentioned about? Well, Kahl describes there the rules of the Egyptian writing system. But the main part of the book is the huge sign list of all hieroglyphs of the Early Dynastic Period!

Jochem Kahl is involved in two other major tools for the study of the inscriptions of the Early Dynastic Period. In 1995 he presented together with Nicole Kloth and Ursula Zimmermann a collection of all inscriptions of the 3rd Dynasty. On the left is an illustration of the text, on the right the transcription and translation. Detailed indexes complete this excellent resource. In addition, since 2002 he has published a dictionary of early Egyptian language. Unfortunately, nothing has been published since 2004. So you can only look up words up to the initial letter ẖ. But up to that point the work is simply brilliant. Dates of occurrences, writings and facsimiles of sources. Fantastic! Moreover, even the vocabulary of personal names is made accessible. For example, on page 291 there is the entry ḥjp, “hurry, run,” with the occurrence in the personal name Ḥjp-kꜣ=j. We will see below why I emphasize this.

Speaking of personal names: There is no separate work on early personal names, nor on titles. However, one can consult the books that deal primarily with the Old Kingdom: Scheele-Schweitzer’s work on personal names also considers those of the 3rd dynasty, and Jones also lists titles of the Early Dynastic Period.

Finally, there is a wonderful palaeography by Ilona Regulski which gives the epigraphic range of all signs.

Let us summarize the cited works here, quasi as an introduction for all those who are interested:

| Theme | Work |

|---|---|

| Database of Early Dynastic inscriptions | Regulski, Database of Early Dynastic inscriptions |

| Dictionary | Kahl, Frühägyptisches Wörterbuch. 2002-2004 |

| Inscriptions of the 3rd Dynasty | Kahl, Kloth, Zimmermann, Die Inschriften der 3. Dynastie. Eine Bestandsaufnahme. 1995 |

| Numbering system of inscriptions | Sperveslage, Die frühen Inschriften Ägyptens. Eine Konkordanz der Nummerierungssysteme. 2021 |

| Onomastics | Scheele-Schweitzer, Die Personennamen des Alten Reiches. Altägyptische Onomastik unter lexikographischen und sozio-kulturellen Aspekten. 2014 |

| Palaeography | Regulski, A Palaeographic Study of Early Writing in Egypt. 2010 |

| Titles | Jones, An Index of Ancient Egyptian Titles, Epithets and Phrases of the Old Kingdom. 2000 |

| Writing | Kahl, Das System der ägyptischen Hieroglyphenschrift in der 0.-3. Dynastie. 1994 |

Of course, this is not an exhaustive list (yes, yes, the works of Kaplony, Morenz or Wilkinson are also important, of course), but it should serve as an introduction to the subject for those who are interested. Secondly, these works should be consulted when dealing with inscriptions of the Early Dynastic Period. For lexical questions, Kahl’s dictionary should be consulted. To research personal names without evaluating the work of Scheele-Schweitzer is negligent. People, refer to these works. If you do not, your conclusions are open to attack. We will see that below!

And the research continues. Recently, a volume in the IBAES series has appeared, in which two articles are relevant to us. Gunnar Sperveslage presents a project to digitally record inscriptions in the essay Methodische und technische Überlegungen zur digitalen Erfassung der Frühzeitinschriften. The new TLA already contains this data! I’ll link to it below for the blog! In addition, this project is also working on the Early Period sign inventory, as described in the second article. We can look forward to the results of this project.

Okay, so what is this about? Well, this blog was born out of anger about an article that tries to explain away the results of the Early Dynastic inscriptions by using a highly impure manner. My goal in this blog is to emphasize the relevance of the Early Dynastic inscriptions for general questions in Egyptology. The study of the Early Dynastic Period produces solid results that cannot be swept aside so easily. This is by no means a second division of Egyptology. And finally: It is more than wrong to consider the findings of the Early Dynastic Period on the basis of circumstances that took place more than two thousand years later, without taking seriously valid internal, i.e. contemporary, explanations. I am the defensor saeculi antiqui here.

General remarks

The article is Quack, Joachim Friedrich: “Nochmals zum Lautwert von Gardiner Sign-List U 23”, published in the current issue of LingAeg. This article has some history. Already in 2003, Quack published a paper dealing with the phonetic value of 𓍋. Based on certain spellings from the first millennium and a pun from the Pyramid Texts, he postulated the reading mḥr for 𓍋. This approach was later contradicted: Ilona Regulski cited two inscriptions from the Early Dynastic Period in which a 𓌸 functions as a complement for 𓍋, cf. Regulski, A Palaeographic Study of Early Writing in Egypt. 2010, p. 196. Simon Schweitzer, Zum Lautwert einiger Hieroglyphen. In: ZÄS 138, 2011, pp. 142-144 mentions two other inscriptions from the Early Dynastic Period that also confirm the phonetic value mr. This new paper by Quack again compiles his evidence for mḥr and attempts to refute the circumstantial evidence from the Early Dynastic Period. Thus, we have here the following sequence: 1) an assertion by Quack 2) a critical examination of his thesis by other Egyptologists 3) Quack attempts to support his original thesis and refute the objections. Such a sequence is found several times in Quack’s œuvre: Quack’s view on embalming and the court of the dead in the Insinger papyrus (Balsamierung und Totengericht im Papyrus Insinger. In: Enchoria 25, 1999, pp. 27-38) has been contradicted by Stadler (War eine dramatische Aufführung eines Totengerichts Teil der ägyptischen Totenriten? In: SAK 29, 2001, pp. 331-348 & Zwei Bemerkungen zum Papyrus Insinger. In: ZÄS 130, 2003, pp. 186-196) and Smith (Traversing Eternity. 2009, pp. 26-27). Quack’s replication of this is Nochmals zu Balsamierung und Totengericht im großen demotischen Weisheitsbuch. In: Enchoria 34, 2014/2015, pp. 105-118. Quack claims in Gibt es einen stammhaften Imperativ ꞽyi̯ im Mittelägyptischen? In: LingAeg 12, 2004, pp. 133-136 that there is no stem imperative of jyi̯. Schweitzer (Nochmals zum stammhaften Imperativ von jyỉ̭/jwỉ̭. In: LingAeg 16, 2008, pp. 319-321) and others have listed some examples of a stemmed imperative. It is this evidence that Quack, Nochmals zum angeblichen stammhaften Imperativ **iyi ‘komm!’. In: LingAeg 24, 2017, pp. 101-110 attempts to refute. So this is not the first time that Quack cannot convince Egyptologists with his first article, but has to publish a second one. It will be interesting to see how Quack will react to the article Smith, New Perspectives on the Book of Thoth. In: OLZ 117, 2022, pp. 271-296, which criticizes Quack in a very substantial way.

Before I get to the content, a few words about the form. Quack is always very apodictic when it comes to judging the opinion of other Egyptologists when they do not follow his opinion: “Die Polemik von Takács (2008: 362 und 366) mißversteht nicht nur Details meiner Argumentation, sondern ermangelt vor allem jedes Erklärungsmodells für die unbestreitbar vorhandenen Schreibungen mit Einkonsonantenzeichen ḥ und h für in anderen Fällen mit dem Schriftzeichen 𓍋 geschriebene Wörter. Eine eigene Auseinandersetzung mit ihr scheint mir deshalb unnötig.” (p. 271, fn. 5) “Vgl. auch Noonan (2019: 102f.), der die neuere Diskussion um den Lautwert des Kopf-Zeichens nicht wahrgenommen hat und mit mäßigen Argumenten versucht, die bei der traditionellen Lesung bestehende Irregularität der Vertretung von ägyptischen t durch hebräisches ṭ herunterzuspielen.” (p. 274, fn. 20) “S. auch Breyer (2019: 117f.), der ebenso gerade den wichtigen Punkt nicht sieht, daß die Lesung der Kopf-Hieroglyphe als tp oder ṭp noch zur Diskussion steht […].” (p. 274, fn. 20) There is nothing to be said against direct language, such as Quack uses, if he supports his judgments by clean argumentation. But it is precisely clean argumentation that is lacking in this article. Facts are not treated in their entirety. Rather, aspects that do not support his thesis are omitted. The work is abbreviated and thus unclean. We will see this again and again in the course of this text. Here is just one example as an introduction, which has nothing to do with the question of the phonetic value of 𓍋. Simon Schweitzer, in his article on the phonetic value of 𓍋, had also dealt with the phonetic value of 𓁶. He concludes that one must stick to the traditional reading tp. Folks, whether you read tp or dp, the issue now is argumentation. If words that spell 𓁶 have survived in other writing systems, one could deduce how to read 𓁶. Schweitzer (p. 134) writes:

Die Verbindung[fn. 24] zwischen dem neuassyrischen Traumdeuter ḥarṭibi [sic!] und 𓁷𓂋𓏭𓁶𓏤𓀀, „Oberhaupt“[fn. 25] ist wohl kaum aufrecht zu erhalten, da sich die jeweilige Bedeutung stark unterscheidet[fn. 26]. Das im Alten Testament erscheinende ḥarṭummim, das seit Stricker[fn. 27] gerne als Wiedergabe von 𓁷𓂋𓏭𓁶𓏤𓀀, „Oberhaupt“ gesehen wird, listet Werning als Beleg für den Ansatz von d auf[fn. 28]. Jedoch ist diese Gleichung mit Lambdin[fn. 29] aus phonologischen Gründen und mit Goedicke[fn. 30] aus semantischen Gründen abzulehnen.

Thus, according to Schweitzer, there are semantic reasons and, in the case of ḥarṭummim, additional phonological reasons against an equation.

Quack also discusses representation in foreign languages. He writes:

Da dieser Punkt für die Lesung von 𓍋 keine zentrale Rolle spielt, erspare ich mir eine Detaildiskussion, obgleich kritisch gesagt werden muß, daß Schweitzer bei der Diskussion über die Lesung der Kopfhieroglyphe zu Unrecht die eklatant richtige Entscheidung von akkadisch ḫarṭibi und hebräisch ḥarṭummim (Plural) zu ägyptisch ḥrꞽ-ṭp verwirft,[fn. 20]

Footnote 20 states:

Schweitzer (2011: 134). Die Behauptung, die Worte paßten semantisch nicht zusammen, ist definitiv nicht zutreffend, wie die Rolle eben des ḥrꞽ-ṭp als Magier und Ritualspezialist in der demotischen Literatur (einschließlich des hieratisch geschriebenen pVandier) deutlich zeigt, s. Holm (2013: 104-114); Escolano-Poveda (2020: 243f.); Quack (iDr.). […]

Whether the words fit together semantically or not is not important to us. We are only interested in how Quack argues. In the text he writes that the equation is wrongly rejected. But the footnote proves this only for semantics. Quack says nothing about phonology. But phonology was Schweitzer’s central point, along with semantics, for rejecting the equation. So the footnote only gives the appearance of a complete refutation of Schweitzer. But without the treatment of phonology, this is not possible at all. So the footnote is just a sloppy trick to support the claim “daß Schweitzer bei der Diskussion über die Lesung der Kopfhieroglyphe zu Unrecht die eklatant richtige Entscheidung von akkadisch ḫarṭibi und hebräisch ḥarṭummim (Plural) zu ägyptisch ḥrꞽ-ṭp verwirft.” Crucial facts are simply omitted from the argument when the desired result requires it. The consideration is selective. This impurity is not an isolated case, as we shall see! One has to look at every quoted discussion in the original, because one cannot know whether the one in Quack’s presentation is distorted.

𓍋 in Early Dynastic inscriptions

Now to the content: I will discuss the four occurrences from the Early Dynastic inscriptions and prove that they all support the phonetic value mr. In addition, I will list other evidence from the Early Dynastic inscriptions.

Title 𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡

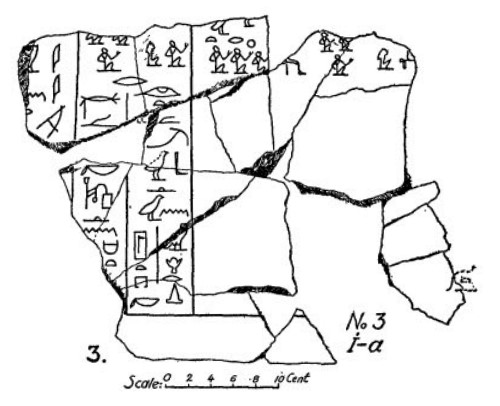

Lacau and Lauer (Lacau, Lauer, La pyramide à degrés IV.1. Inscriptions gravées sur les vases. 1959, pl. 22.121 & pl. 22.122) published in 1959 two vessels from the 2nd dynasty which both carry a column with an inscription. These are the inscriptions with IDs 2140 and 2141, and the images are online at https://archive.org/details/LacauLauer1959/page/n55. The title ḥm-nṯr-Spd.w is followed by a 𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡, where Lacau and Lauer were only able to identify the first two characters as the title. Kaplony, Eine Schminkpalette von König Skorpion aus Abu ‘Umûri. In: Or 34, 1965, pp. 139-140, fn. 1, recognized that it was smr-wꜥ.tj. All other scholars have followed his view, cf. Kahl, Wörterbuch, p. 109; Kahl, System, p. 740, fn. 2341. Sperveslage transcribes and translates the beginning of the inscription as follows:

𓇮𓅏𓊹𓍛𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡𓈖𓉐𓈖𓂓

ḥm-nṯr-Spd.w smr-wꜥ.tj N(.j)-Pri̯-n(=j)-kꜣ(=j)

Priester des Sopdu, Einziger Freund, Ni-per-ni-kai

https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/sentence/ICEASEXYKBLjoUFFjJHo90aiTwk & https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/sentence/GO7IM5SWTFGGZMICT5NDUUB4BI

The complementation with 𓌸 is unusual. Regulski justifies convincingly:

Two hard stone vessels from Saqqara (2140-41), probably dating to the Second Dynasty, render the title śmr wꜥ.ty in ḥm nṯr Śpd.w śmr wꜥ.ty “prophet of Sopdu, sole friend”, followed by a personal name and a place name. [fn. 2069] The orthography of śmr is highly unusual but particularly interesting in this respect. The phonetic value mr is represented twice; by 𓍋 (U23) to the left of the central placed 𓋴 (S29), and by 𓌸 (U6) to its right side. The reason why is obvious; to avoid confusion with other scepter-signs (S42, T3, and V24), which all looked alike in the Early Dynastic period (p. 185). By adding an ideogram with the same phonetic value[fn. 2070], such misunderstanding was avoided.

The two inscriptions are a central witness for the reading of 𓍋 as mr. Quack, so if he is to maintain his reading mḥr, he must invalidate these passages. He has four objections:

- It is not certain that 𓌸 really belongs to the title. Lacau and Lauer have not yet assigned 𓌸 to the smr title.

- Palaeographically, it is not certain whether the flat sign after 𓌸 is really to be understood as a harpoon with the phonetic value wꜥ and whether 𓍋 is really to be read.

- The interpretation of the personal name is uncertain.

- The position of 𓋴 after 𓍋 is singular.

In detail:

First objection

This is a very weak argument. It would mean that knowledge can only be considered certain if the editio princeps lists it. Should we doubt all the progress that Quack made in reading the Book of Thoth just because Zauzich and Jasnow read differently? Obviously, there is a title at the beginning of the inscription, so one might expect a sequence of titles and personal names. Regulski explains, as quoted above, why the 𓌸 is here. If the 𓌸 did not belong the smr, there would be no way to read the inscription. What title beginning with 𓌸 should follow the smr? Quack offers no alternative. But that would be necessary to shake Regulski’s plausible explanation. It is also inexplicable that Quack does not mention Regulski’s argument in his discussion of these two inscriptions. He simply omits it. This unclean selective argumentation of Quack is only understandable if he sees no possibility to invalidate Regulski’s explanation of the 𓌸.

Second objection

The flat sign after 𓌸 is - according to Kahl, System, pp. 741-742 - a t1, which represents a “einzackige Harpune”. Contrary to Quack’s assertion, the shape of the hook is not at all unusual, as can be seen in Regulski, pp. 648-649. Quack erroneously refers to page 628. Whether the forms present there led him to this untenable statement? The tall narrow sign before 𓋴 could indeed be confused with other scepter signs. Therefore the complementation with 𓌸 makes sense. This is where Quack really should have addressed Regulski’s argument. By the way, the complementation with 𓌸 is not singular, see below.

Third objection

The form of inscription is a sequence of titles followed by a personal name. Even if the interpretation of the personal name is problematic, this does not affect the titles. Of course, a N.j + X is unusual, since X is a personal name and not the name of a god or king. But such a name pattern is attested in the Old Kingdom, cf. N.j-Ꜣbbj https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/850877 Probably there will be more cases from the 3rd millennium, but they cannot always be recognized because of the possible defective writing of nisba n.j (on this Scheele-Schweitzer, Personennamen, p. 151).

Fourth objection

Quack wonders about the sequence 𓍋𓋴 and thinks that it is singular. This is completely unfounded. Here some examples of different words from the Early Dynastic inscriptions, where exactly this sequence 𓍋𓋴 is documented.

| Word | Inscription |

|---|---|

| Ḥw.t-smr.w | 2691; 2692 |

| smr | 1099; 1761; 1764; 2136; 2138; 2139 |

| smr-pr-nzw | 1865 |

| Smr-nṯr.w | 0857 |

| Smr-ẖ.t | 1659; 1670; 1671; 1672; 1705; 1707; 1721; 1724; 1726; 1756 & 1756; 1757; 1799; 1816 & 1821 & 1912; 1827; 4046a-b & 4557; 4048 & 4527; 4444 |

Nowadays it is quite easy to find such spellings. Our metasearch engine for hieroglyphs provides the results. But even earlier it was easy to find them with Regulski’s database.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize: The sequence 𓍋𓋴 is well attested. The palaeographic evidence supports the reading of the flat sign as wꜥ. There is a title sequence that can only be understood if 𓌸 is the complement of 𓍋. With a phonetic value mḥr, this inscription cannot be read. Instead, there is clear evidence for the phonetic value mr.

Personal name 𓅭𓈘𓎛𓍋

Quibell, Archaic Mastabas. 1923, p. 38 published the following inscription (which today has ID 3334) on a vessel more than a hundred years ago: 𓅭𓈘𓎛𓍋. Unfortunately, there is no facsimile and no photo. However, the publication is online: https://archive.org/details/excavationsatsaq06quibuoft/page/38/mode/2up. Kahl, Kloth and Zimmermann, pp. 180-181 published this inscription in their collection of inscriptions of the 3rd Dynasty. They understood this inscription as a personal name and read Mr-Ḥjp.w (?). This interpretation is followed by Sperveslage and Scheele-Schweitzer, #1274, who translates “Geliebter/Kanal des Hapi (?)”. 𓅭 and 𓎛 belong to the name of the god according to this understanding, and the signs 𓈘 and 𓍋 belong to mr. Quack doubts this interpretation. He lists the following objections:

- The question marks prove that the reading is very uncertain.

- The translation “Kanal des Apis” is to be excluded. Quack claims: “so heißt kein Mensch”.

- Mri̯ is not written with 𓈘 alone. Normally 𓌸 is used. When 𓈘 is used, it is only in conjunction with 𓌸.

First and second objection

Indeed, the facts here are not as clear as at 𓇮𓅏𓊹𓍛𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡𓈖𓉐𓈖𓂓. Also Quack is to be agreed that a name “channel of Apis” does not correspond to the usual onomastic practice. However, a “Beloved of Apis” is perfectly consistent with onomastic practice.

Third objection

𓈘 alone is very well attested in the inscriptions, contrary to Quack’s assertion:

| Word | Inscription |

|---|---|

| Mr.y-Ḥr.w | 0971 |

| Mr.t-jb-Nj.t | 0717 |

| Mr.t-Nj.t | 0734; 0735 |

| Mr.t-kꜣ | 0699; 1287 |

| Mri̯=s | 3568 & 3568 |

| Mri̯-nb.wj | 1127; 1128 |

There is nothing wrong with a personal name expressing the element with 𓈘. Above, in the title 𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡, 𓍋 appears together with 𓌸. For another proof of the combination of 𓍋 with 𓌸, see below. In this respect, the combination of 𓍋 with 𓈘 can very well be understood as mr.

Personal name 𓏴𓍋𓁐

The inscription with ID 0689 is an Early Egyptian stela with the following inscription 𓏴𓍋𓁐. This is generally considered to be a spelling of the frequent personal name Mr.t-Nj.t (see the overview of personal names in the first volume of the monumental work Kaplony, Die Inschriften der Ägyptischen Frühzeit. 1963, hereafter: IÄF, here the entry on Mr.t-Nj.t: pp. 493-496): IÄF I, p. 184 and p. 494; Klasens, Een grafsteen uit de eerste dynastie. In: OMRO 37, 1956, p. 18, #40 and p. 22, #40; Sperveslage; Kahl, System, p. 750. Martin, Umm el-Qaab VII. Private Stelae of the Early Dynastic Period from the Royal Cemetery at Abydos. 2011, p. 50, however, reads Sḫm-Nj.t. This is palaeographically conceivable, even though the sign in Regulski’s palaeographic plates fits the examples of U23 rather than S42. No further evidence for the name Sḫm-Nj.t is known, but the formation type Sḫm + name of god is attested, cf. Kahl, System, p. 707, Scheele-Schweitzer, # 3207-3209. Thus, the reading Sḫm-Nj.t cannot be completely ruled out, but a Mr.t-Nj.t is clearly more probable on the basis of the evidence and the palaeography. Pätznick, Ab Hor, le “Désiré d’Horus”, et le poisson silure électrique tacheté. In: Apprivoiser le sauvage / Taming the Wild. 2015, p. 287 reads this name Ꜣb-Nj.t. Quack follows him and translates: “die Ersehnte der Neith”. He rightly objects that this name “zwar sonst unbelegt ist” (p. 282). Furthermore, even the formation type Ꜣb/Ꜣb.t + name of the gods is completely unattested, as a look at the overview in Kaplony and a look at the standard works Ranke and Scheele-Schweitzer proves. Kahl’s dictionary, which also breaks down the components of personal names, does not mention any verb ꜣb. Only ꜣbw “panther” is attested in personal names, cf. Kahl, System, p. 750. Why does Quack not consult Kahl’s works here? Is it because Kahl knows no ꜣb, so that Quack’s argumentation is weakened? Why does Quack not write how unlikely the reading Ꜣb-Nj.t is, because there is no such formation pattern? Instead, he discusses whether Nj.t or Ḥmws.t should be read. This is not relevant to the reading of 𓍋; for whether it is Mr.t-Nj.t or Mr.t-Ḥmws.t: it remains with a proof for the reading mr.

Conclusion on Regulski’s and Schweitzer’s evidence

We hold: A re-examination of the Early Dynastic cases mentioned by Regulski and Schweitzer supports the phonetic value mr. Quack’s attempts to invalidate the evidence have all failed.

Further evidence

In addition, there are four other indications that support a phonetic value mr in the Early Dynastic Period:

- The king’s name Narmer is mostly written with a fish sign and 𓍋. Usually both signs are also arranged in a serekh. Sometimes, however, only the fish is inside the serekh, while the 𓍋 is outside, e.g. 0089. Petrie, Tarkhan II. 1914, pl. 20.2 published an inscription (ID: 0109) from Tarkhan more than 100 years ago in which a sign resembling a hoe (and not the 𓍋) is outside the serekh. Petrie interpreted the sign as 𓌸. His conclusions about the reading are not relevant here. If one follows Petrie, one would have here a spelling of the king’s name Narmer with the hoe instead of the 𓍋. Kaiser, Einige Bemerkungen zur ägyptischen Frühzeit. III. Die Reichseinigung. In: ZÄS 91, 1964, p. 93, fn. 3, doubted the reading mr. He recognized in the sign outside the serech a šnꜥ. Gilroy, ‘Forgotten’ Serekhs in the Royal Ontario Museum. In: GM 180, 2001, pp. 67-76, who published an inscription quite similar to the one from Tarkhan, followed Kaiser’s interpretation. However, two reasons argue against the identification as šnꜥ. First, šnꜥ is understood as a storehouse. However, other inscriptions from Narmer describing administrative units formed with the king’s name are not known. Only once is a plantation attested with early kings: 4015. Second, palaeographically, the šnꜥ-sign looks quite different in Early Dynastic inscriptions, as the evidence in Regulski, p. 655 clearly shows. The mr hoe, on the other hand, resembles this sign under the serekh, even though one stroke is very long. This may be due to the fact that the sign is thus adapted to the width of the serekh. Thus, Kaiser’s suggestion to read šnꜥ here no longer seems plausible. Rather, one must recognize the mr hoe here. This provides new evidence for the interchangeability of 𓍋 and 𓌸.

- Kaplony lists a Mr-nṯr in his compilation of early personal names (IÄF I, p. 497). This name has several occurrences and is written 𓍋𓂋𓊹. Kahl follows Kaplony’s reading, albeit with a question mark: Kahl, System, p. 750. The meaning of the name is “beloved of the god.” This name also appears in the Old Kingdom, cf. Scheele-Schweitzer, #1317. The database AGÉA, which collects names of the Old Kingdom and lists 1772 entries so far (Scheele-Schweitzer has a total of 3893 entries in her book, more than twice as many!), understands the early name as ꜣb-nṯr and translates “Celui qui a été désiré par le dieu.” It is curious that Kaplony’s discussion is not received and that the dating to the 2nd Dynasty made by Helck, Die Datierung der Gefässaufschriften aus der Djoserpyramide. In: ZÄS 106, 1979, pp. 120-132 is not taken into account. Since - as noted above - the verb ꜣb is not attested at all in the Early Dynastic Period, this reading is not probable.

- Amélineau, Les nouvelles fouilles d’Abydos 1895-1896. 1899 published an inscription with the name of King Semerkhet, which Gauthier included in his Livre des Rois, I, p. 12: https://archive.org/details/MIFAO17/page/n19. It is number 33 on the plate between pages 198 and 199. This is online at https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.3439#0238. If the illustration is to be trusted, there is another 𓌸 above 𓍋𓋴. Only with a phonetic value mr for 𓍋 the inscription can be explained!

- Sperveslage recently discussed in his very readable article Three Lines on the Jar: A Note on a Term for Oil and a Reinterpretation of a Proposed Predynastic Royal Name. In: Early Egyptian Miscellanies: Discussions and Essays on Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt. 2022, pp. 199-205 various spellings of mrḥ.t fat. He was able to show convincingly that the spellings 𓍋𓈗 (Sperveslage, p. 200, fig. 9: 0155), 𓍋𓌸𓎛 (Sperveslage, p. 203, fig. 10: 1869b), and 𓎛𓌸 (Sperveslage, p. 203, fig. 11: 4452) are all mrḥ.t. The spelling of 𓍋𓌸𓎛 is particularly noteworthy: The 𓌸 here acts as a complement to the 𓍋. A phonetic value mḥr for 𓍋 cannot explain the spellings.

Metathesis

We have just seen that mrḥ.t can be written with 𓍋. So now is the right time to discuss an idea of Quack. He suggests that metathesis occurs in some cases for words written with 𓍋. However, this is not a separate section within his article. Instead, he treats this issue in several places. He proposes the following cases:

- mḥr → mrḥ or mrḥ → mḥr

- mḥr → ḥrm → πυραμίς &هَرَم

First the first case. Quack writes about the personal name 𓅭𓈘𓎛𓍋:

Hinzu kommt die Frage, ob hier eventuell über die Grenze der Bestandteile hinweg eine Lautfolge mrḥ mit 𓍋 angegeben wird, was dann lediglich eine Metathese zu dem von mir angesetzten Lautwert mḥr wäre. (p. 282)

In the case of the personal name 𓏴𓍋𓁐, Quack is of the opinion that it does not contain the name of the god Nj.t, but Ḥmws.t. He writes:

Damit eröffnet sich aber erneut die Option, daß über die Grenzen der Einzelbestandteile hinweg die Lautfolge mrḥ mit 𓍋 ausgedrückt wurde. (p. 283)

It should be noted that the writing of a grapheme across word boundaries postulated by Quack is not attested in the inscriptions of the Early Dynastic Period. Thus, these two cases are by no means a reliable source for metathesis. Finally, in footnote 83 on page 283, he states:

Prinzipiell ist es auch denkbar, daß mrḥ ursprünglicher ist und mḥr die Metathese davon darstellt.

Assuming an original phonetic value mrḥ, one could well explain the spellings of the word mrḥ.t compiled by Sperveslage. In 𓍋𓌸𓎛, 𓌸 is the complement of 𓍋, regardless of whether the phonetic value of 𓍋 is mrḥ or mr. Also the title 𓍋𓋴𓌸𓌡 does not contradict a reading mrḥ, here too 𓌸 would be a complement of 𓍋. However, the mentioned spellings of the personal name Mr-nṯr with 𓍋 and the spellings of the kings Narmer and Semerkhet with 𓌸 cannot be explained.

In general, however, the idea of metathesis does not seem to be fully thought through and is fraught with serious problems. For example, if we assume that originally the phonetic value was mrḥ, that is, that the evidence for 𓍋 from the Early Dynastic Period is to be read as mrḥ, we must postulate that originally the title was smrḥ and the verb “to be ill” was mrḥ, for both words are attested in the inscriptions of the Early Dynastic Period. However, both words continue to be spelled 𓍋, so metathesis must have occurred at a similar time for both words. Otherwise, one would expect spellings that indicate the process of metathesis. There are many examples in Egyptian inscriptions where an earlier and a current state are represented at the same time. For example, when the sound r is lost, a mixed spelling 𓂋𓇋 is offered for the verb zwr “to drink”. There are also spellings of pẖr that have a 𓈙𓄡. Finally, there are hybrid spellings for verbs ultimae ꜣ: 𓊃𓌳𓄿𓅓𓌪𓂡. None of this happens for words written with 𓍋. There is no graphical reflex for the metathesis mrḥ → mḥr. Furthermore, metathesis certainly depends on parameters such as vocalization and syllable structure. If the vocalization or syllable structure is different, metathesis should not be effective. However, this means that the assumption of metathesis mrḥ → mḥr must assume the same vocalization and the same syllable structure of the title and the verb “to be ill”. Finally, it is necessary to consider how long the process of metathesis took. Quack thinks that in the Old Kingdom the word for pyramid was mḥr. His supposed evidence will be rejected below. At the same time he claims:

[…] und für die Lautform als mrḥ gibt es auch in den Sargtexten gewisse Indizien.[fn. 84] (p. 283)

How can metathesis be completed in the Old Kingdom with the word “pyramid,” but still be mrḥ in the Middle Kingdom? It does not make any sense. The idea of metathesis is purely an ad hoc explanation that does not stand up to scrutiny.

Finally, the second metathesis proposed by Quack: He posits this in order to derive the Greek and Arabic word for pyramid from an Egyptian ḥrm. However, the etymological circumstances of these words are not entirely clear, so that the assumption of metathesis is quite speculative. In fact, neither the Greek nor the Arabic word is certain of an Egyptian origin.

Conclusion

In summary, the following results: the evidence of the Early Dynastic Period is unambiguous, 𓍋 has the phonetic value mr. The refutations that Quack attempts have all failed and rather reveal a certain ignorance of the matter of the Early Dynastic inscriptions. My colleague Peter Pathappan has collected several cases from the Old and Middle Kingdom that also argue for the reading mr. He will publish this soon.

Quack’s supposed evidence from the Old and Middle Kingdom

On pages 275-281, Quack lists many cases that he believes support the phonetic value mḥr: some from the Old Kingdom, one from the Middle Kingdom, and quite a few from after the New Kingdom. Here I will consider these cases chronologically, easily refuting those from the Old and Middle Kingdom and explaining those from the New Kingdom onward.

Urk. I, 275.2-3

The main Old Kingdom witness to the supposed phonetic value mḥr is an inscription from the mortuary temple of Menkaure published by Reisner, Mycerinus. 1931, pl. A, #3: https://gizamedia.rc.fas.harvard.edu/images/MFA-images/Giza/GizaImage/full/library/reisner_gn_books/mycerinus/reisner_mycerinus.pdf#page=305.

Here we have a split column. The elements of both columns are thus parallel and jointly dependent on the genitive n.w. Edel, Altägyptische Grammatik. 1955/1964, § 755 reads the first split column in the following context:

𓂝𓄏𓃀𓅱𓏛𓈖𓅱𓅓𓁷𓂋𓉴𓎡 ꜥbw njw m ḥrk “Reinigung(szeremonie) in deiner Pyramide”

The 𓎡 is not in the first split column, but in the second. However, all scholars (Sethe in Urk. I, 275.2-3; Edel; Goedicke; Collombert; Bogdanov) assume that the =k refers to both elements of the split column. The only epigraphic justification for this assumption is the size of the sign 𓎡 projecting into the first split column. However, it remains questionable whether this justification is sufficient to include the =k in the first split column.

Goedicke, Königliche Dokumente aus dem Alten Reich. 1967, p. 78 translates as follows:

um den Kult[fn. 3] in deiner Grabanlage[fn. 4] und deines Heiligtums zu machen[fn. 5].

In note 5, Goedicke writes:

𓈖𓅱𓅓 ist befremdlich

This - at first sight - inexplicable 𓅓 tempts Collombert, 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴 = 𓁷𓂋𓉴 = 𓅓𓁷𓂋𓉴 = (m)ḥr, “pyramid” ? In: GM 227, 2010, pp. 17-22 to postulate an mḥr. He translates the passage as follows:

faire les purifications de ta pyramide et de ton temple (p. 18)

Here, the 𓅓 is supposed to represent the beginning of the noun mḥr. Edel had a different idea of how this 𓅓 should be understood. He quotes this passage in his paragraph § 755, where he explains that prepositional expressions can be used like nouns by appearing in the indirect genitive. Collombert comments on this explanation as follows:

E. Edel[fn. 6] essaie de contourner la difficulté de la sequence n.w (génitif indirect pluriel) + m (préposition) en supposant une substantivation de la préposition, similaire à la construction du type jmꜣḫw.t n(.t) ḫr ḥw.t-ḥr, “pensionnée auprès d’Hathor”. Cette dernière construction est bien attestée mais constitue cependant un cas très particulier ; la preposition ḫr y est probablement employée comme une sorte d’élement amortisseur, introduisant une marque de déférence devant la mention d’un personnage important (ici une déesse, mais parfois aussi le roi, comme dans la formule ḥsw.t n.t ḫr-nsw) et s’est probablement figée dans cet emploi. De fait, E. Edel ne peut citer aucun exemple parallèle à la construction * n m ḥr qu’il propose. (pp. 18-19)

Collombert thus criticizes the idea that there can be an expression genitive + prepositional expression. He considers the well-attested construction with the preposition ḫr to be ossified. Since he lacks parallels, he is not convinced that there is an expression with genitive + preposition m. Consequently, because of this rejection, Collombert must combine the 𓅓 with the following hieroglyphs into one word.

Bogdanov, The Old Kingdom Evidence on the Toponym ḫntj-š “Lebanon”. In: Ägypten und Levante 29, 2019, pp. 125-148 does not follow Collombert. He writes:

Nevertheless, the examples he gave are insufficient to postulate the hypothetical compound mḥr “pyramid”. The first example he gave from the Sixth Dynasty decree Giza II[fn. 59] can be explained by layering of the prepositions nw /m in the documentary form:[fn. 60] (p. 131)

He considers the co-occurrence of the genitive and the 𓅓 to be a mere error. He writes:

Similar examples of errors in the documentary form can be found in the Dahshur decree, 13, 14:[fn. 61] … 𓅓𓉗𓉐𓈖𓏏𓅓𓊖𓏏𓉴𓉴𓊪𓏏𓈖 … m ḥwt n(j)t {m} njwtj (j)ptn(j) “… in the temple {in} of these two pyramid towns”; however, the phrase is possible to read ḥwt nt(jt) m… “temple which is in…” … 𓐍𓏏𓆑𓎗𓅱𓏏𓈖𓎗𓅱𓏛𓄋𓊪𓏏𓏛𓈖𓅓𓊖𓏏𓉴𓉴𓊪𓏏𓈖 … ḫftj wḏt n wḏ wpt n {m} njwtj (j)ptn(j) “… in accordance with a decree of assignment ordered for {in} these two pyramid towns.”

The layout of the Dahshur decree proves that the 𓅓𓊖𓏏𓉴𓉴𓊪𓏏𓈖 is to be read for several columns. Bogdanov thus knows of other cases where the indirect genitive is followed by the preposition 𓅓. However, he considers this to be an error. Instead, there are other examples of the construction here, which Edel explains in § 755. Thus the 𓈖𓅱𓅓𓁷𓂋𓉴𓎡 that Edel cites is no longer singular. So there is no longer any reason to consider the 𓅓 after an indirect genitive as the first sign of a noun! De facto, the supposed main witness is not a main witness at all. In any case, there is no sound evidence here that one should read the sign 𓍋 mḥr.

MFA 31.248 + 31.249

The second evidence Collombert lists is also untenable. He understands a […] 𓁹𓏏𓋴𓅓𓅓𓁷𓂋𓉴𓉻𓈖 […] as:

“… la faire dans la pyramide principale pour …” (… jr.t=s m mḥr ꜥꜣ n …) (p. 20)

The textual context is very fragmentary, but nevertheless the suffix =s seems very unlikely. What, after all, should it refer to? Accordingly, the interpretation of Brovarski, Once More ḥr, ‘Pyramid’? In: Sitting Beside Lepsius. Studies in Honour of Jaromir Malek at the Griffith Institute. 2009, pp. 98-114 is preferable. He reads:

… what the sem-priest did on[fn. g] the principal pyramid[fn. h] for … (p. 105)

This corresponds to a jr.t sm m ḥr ꜥꜣ n … This eliminates all the approaches Collombert offers to postulate a mḥr in the Old Kingdom.

JE 52001 C

Quack sees a passage from the papyrus Cairo JE 52001 C, namely oraec1844-6 as further support for the phonetic value mḥr: dmḏ n kꜣ.t 𓈖𓏏𓅓𓁷𓂋𓉴 ꜥꜣ. Posener-Kriéger translates in her editio princeps (Fragments de Papyrus Provenant de Saqqarah. In: RdÉ 32, 1980, pp. 83-93): “Total de travaux qui ont lieu à la pyramide principale” Brovarski, p. 104, follows this interpretation and transcribes: dmd n kꜣt nty m ḥr ꜥꜣ. Hafemann translates similarly: “Die Gesamtheit der Arbeit, die im großen Pyramidenplateau (zu machen)ist:” She offers furthermore the following comment for the 𓈖𓏏 in the old TLA:

Bezugswort dmD

Quack questions the unanimous interpretation as a relative pronoun and ponders:

ob man dies als kꜣ.t n.t mḥr oder als kꜣ.t n.tꞽ m ḥr segmentiert. Die Tatsache, daß in der vorangehenden Spalte in der Überschrift eindeutig kꜣ.t n.t sꜣḫ ꞽnb steht, also mit indirektem Genitiv, nicht mit Relativsatz konstruiert wird, stellt ein schwerwiegendes Argument zugunsten der ersten Lösung dar. (p. 275)

Quack thus presents two options: kꜣ.t n.t mḥr and kꜣ.t n.tj m ḥr. The second variant, however, is grammatically incorrect. The relative pronoun would have to be feminine, since it follows the genus of the reference word. However, this problem is solved by looking at the whole phrase. This is because kꜣ.t is included in the phrase dmḏ n kꜣ.t . So the relative pronoun can refer to the masculine dmḏ, as Hafemann notes. Why does Quack abbreviate here, suppressing the grammatical impossibility of his second option? This looks a bit like sleight of hand. For if he omits the dmḏ, he can more easily postulate a parallelism to another passage with kꜣ.t. But the conclusion that kꜣ.t must follow with indirect genitive because kꜣ.t is so used in another passage is also based on a purely superficial consideration and cannot be sustained. In fact, the construction of kꜣ.t clearly depends on the nature of the dependent phrase. This becomes clear when one looks at the constructions with kꜣ.t in the titles of the Old Kingdom. The patron of the kꜣ.t, that is, the one who benefits from the kꜣ.t, is attached with the genitive. jm.j-rʾ-kꜣ.t-n.t-nzw “overseer of the king’s works,” jm.j-rʾ-kꜣ.t-nb.t-n.t-nswt “overseer of all works of the king.” Similarly, the type of activity is constructed with the genitive. mḥnk-nzw-m-kꜣ.t-jr.w-ꜥn.t “intimate of the king in the works of manicuring/care of hands and nails,” mḥnk-nzw-m-kꜣ.t-jr.w-šn “intimate of the king in the works of hairdressing.” The places, on the other hand, where the kꜣ.t is performed are connected with the preposition m: jm.j-rʾ-kꜣ.t-m-ḥw. t-nṯr “overseer of works in the temple,” jm.j-rʾ-kꜣ.t-m-spꜣ.wt-ḥr.jwt-jb-Šmꜥ.w “overseer of works in the Middle Nomes of Upper Egypt.” This tendency is evident, although there are isolated outliers, cf. Jones, #952. Thus, when a kꜣ.t at the pyramid is reported, it is to be expected that the word for pyramid is connected with the preposition. However, in what Quack considers a parallel phrase, the kꜣ.t is followed by an infinitive describing an activity - however it is to be understood here exactly. This means: the supposed parallelism does not exist at all. Instead of postulating a mḥr one should better read here preposition m with the following noun!

Quack also quotes another 𓅓𓁷𓉴𓆑. However, Quack considers the context to be too incomplete. In fact, one could also simply recognize the preposition m-ḥr here with a following logogram.

Word play

Finally, Quack quotes the sentence oraec861-17 from the Pyramid Texts (PT 600): m ḥri̯ jr =f m rn =f n(,j) 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴. He sees this as a confirmation of the phonetic value mḥr; for the play on words (m ḥri̯ on one side and 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴 on the other) is only possible if the pyramid is to be read mḥr. Schweitzer, in his article mentioned above, had discussed the different types of sources that can help to find out the phonetic values of signs. He categorically rejects word plays:

Augenscheinlich kann man mit Wortspielen jede gewünschte Lesung bestätigen. Für eine Bestimmung des Lautwertes ist es damit ungeeignet und sollte nicht herangezogen werden. (S. 133)

Quack takes up this criticism and distinguishes two kinds of word plays. One type he calls “explicit” because the Egyptians themselves indicated that a word play was present. The other type of word plays are those that are discovered by modern scholars without being indicated by the ancient scribe. Quack now considers only the explicit word plays as reliable witnesses for determining a phonetic value. He quotes on page 277 a possible, but not explicit word play, which he does not want to accept as evidence. He writes about the explicit word play:

Wo dagegen die Ägypter selbst uns explizit angeben, daß ein Wortspiel vorliegt, d.h. insbesondere in der sogenannten Namensformel,[fn. 18] liegt die Sache anders; hier ist grundsätzlich von einer Lautkorrelation auszugehen,[fn. 19] und entsprechend haben solche Stellen im Zweifelsfall auch argumentatives Gewicht. (p. 274)

Let’s take a closer look at the name formula, to which the above mentioned theorem m ḥri̯ jr =f m rn =f n(,j) 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴 belongs. The most important work on the name formula is Hellum, In Your Name of Sarcophagus: The ‘Name Formula’ in the Pyramid Texts. In: JARCE 51, 2015, pp. 235-242. Quack, surprisingly, does not cite this article. Hellum discusses this formula at length, and in particular the word play in these phrases. She writes on page 239:

Paronomasia is an essential part of the name formula: every example of the formula in the Pyramid Texts shows some evidence of word play. It occurs invariably between the verb and the name, and the word play lies in the spelling of the word, rather than in its meaning. In the following example, the evidence of word play is obvious in the original:

ṯḥnḥn=k jm=s m-m nṯrw m rn=s pw n ṯḥnt

You should gleam by means of it among the gods, in this its name ı͗f “Faience.” (PT 301 § 454)

The verb ṯḥnḥn “to gleam”[fn. 27] contains the same consonants, bar only the feminine t, to ṯḥnt “faience.”[fn. 28] It is more common than not that, as here, the verb and the name[fn. 29] share a cluster of consonants, most, but rarely all, of which are identical.

The “Lautkorrelation” that Quack is talking about is confirmed by Hellum. But with Hellum you have to assume that not all consonants are identical. A very nice example Hellum gives on page 237 is oraec1238-11 from PT 366: … jmi̯ =k ḏnd m rn =k n(,j) ḏndr,w, “… damit Du nicht zornig bist in Deinem Namen ‘Barke’”. Here the wordplay exists between the verb ḏnd and the name ḏndr.w. Some, but not all, of the consonants are identical. If in these examples the word play does not involve all consonants, then in m ḥri̯ jr =f m rn =f n(,j) 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴 there could also be a word play involving only some consonants.

Quack, however, claims:

Wie oben ausgeführt, müssen derartige explizite Wortspiele mit der Namensformel m rn=f m … ernst genommen werden und zählen als Argumente für die Ansetzung der Lautform - sofern Schweitzer keine Belege dafür geben kann, daß anderswo ein ḥ in einer Namensformel ohne Korrespondenz im ausgedeuteten Wort ist, muß der Beleg als definitive Absicherung der Lesung gelten. (p. 275)

I hope to prove that Quack is wrong here as well. The first proof is the example of Hellum. There is a word play between ṯḥnḥn and ṯḥn.t. The second ḥ is missing in ṯḥn.t. There are other cases where there is not complete agreement regarding ḥ:

| ORAEC | PT spell | sentence | translation | word play |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| oraec2479-9 | PT 356 | jmi̯ =sn ḥm twr ṯw m rn =k n(,j) jtr,t.du | They will certainly not reject you in your name ‘The Two Chapels’. | (jmi̯ =sn ḥm) twr (ṯw) / jtr.tj |

| oraec450-9 | PT 357 | m-ẖnw ꜥ(.wj) =k m rn =k n(,j) ẖn(w,j)-ꜥḥ | in your arms in your name ‘He In The Palace’ | (m-)ẖn(w) ꜥ(.wj) / ẖn(w.j)-ꜥ(ḥ) |

| oraec1167-40 | PT 364 | fꜣi̯.n ṯw Ḥr,w m rn =f n(,j) Ḥnw | Horus has lifted you up in his name ‘Barque’. | (fꜣi̯.n ṯw Ḥr.w) / (Ḥnw) |

| oraec591-11 | PT 366 | dwꜣ =sn ṯw jmi̯ =k ḥri̯ jr =sn m rn =k n(,j) Dwꜣ-wr | They praised you so that you would not depart from them, in your name ‘Dua-ur’. | dwꜣ (=sn ṯw jmi̯ =k ḥri̯ jr =sn) / Dwꜣ(-wr) |

| oraec1056-11 | PT 593 | šni̯.n =k (j)ḫ,t nb.t m-ẖnw ꜥ =k m rn =k n(,j) Dbn-pẖr-ḥꜣ(,jw)-nb,wt | You held everything enclosed in your arms in your name ‘Circumference surrounding the Hau-nebut’. | (šni̯.n =k jḫ.t) nb.t (m-ẖnw ꜥ =k) / (Dbn-pẖr-ḥꜣ.jw)-nb(.w)t |

| oraec2446-4 | PT 660 | ḏd.n =f ṯni̯ ms.w =(j) jr =k m rn =k n(,j) msn,t ḥr.t | He has said about you “The most excellent of my children” in your name ‘Superior Menset’. | (ḏd.n =f ṯni̯) ms(.w =j jr =k) / ms(n.t) (ḥr.t) |

| oraec257-20 | PT 690 | jni̯ =sn n =k rn =k pw n(,j) Jḫm-sk n ski̯ =k n ḥt(m) =k | They will get you this name of yours ‘Non-sinking’ and you will not sink, you will not perish. | (jni̯ =sn n =k n) sk(i̯ =k n ḥt(m) =k) / Jḫm-sk |

The examples of the name formula, and especially these cases, show that one cannot make any predictions about the form in the name formula. By this I mean the following: If only the beginning of the formula is preserved, one cannot reconstruct what the end is. Accordingly, one cannot predict the exact phonetic form of the elements in the word play. For the reconstruction of the phonetic values, the examples from the name formula are completely worthless.

CT V, 133b

For the Middle Kingdom, Quack cites only one piece of evidence. He writes:

Bemerkenswert ist auch die Schreibung 𓎛𓅓𓂋𓏏𓅪𓈙𓏤𓈇𓏥 CT V 113 b, in welcher das Determinativ des schlechten Vogels nahelegt, daß der Schreiber eine Verbindung zum Wort “krank sein” gezogen hat.

CT V, 133b, however, does not offer a consistent textual tradition. Only T1C has the spelling quoted by Quack. T1Be has 𓌸𓂋𓎛𓏏𓏭𓈙𓈇𓏤𓅱𓏭, while M2C and Sq2C are quite different. To what extent a reference can really be made to a word written with 𓍋 is highly speculative. In other words, this passage from the coffin texts is completely worthless as an argument.

Conclusion

Thus, there is no positive evidence for a phonetic value mḥr in either the Old or Middle Kingdom!

The state of affairs after the New Kingdom

For the post-New Kingdom period, however, Quack offers a variety of evidence using a single consonant sign for ḥ. How can this be reconciled with the clear evidence for the phonetic value mr? The first possibility is phonetic development. This assumes that the words originally read mr or smr are now mḥr or smḥr. This is more than unlikely. First, a development “ø → ḥ” is not otherwise attested in Egyptian, and second, this development would occur only in words written with 𓍋, not in those written with 𓌸. Consequently, in his article on the phonetic value of 𓍋 (p. 143), Schweitzer rejects the idea of a phonetic development from mr to mḥr.

Instead, Schweitzer wants to understand the spellings with a written ḥ as scribal errors. There are two interesting questions here: First, is it plausible that a sign with the phonetic value ḥ could ever have evolved from 𓍋? Schweitzer mentions various misspellings which show that in general there is a possibility that 𓍋 can be written into 𓎛. Second, why do the spellings with the single consonant ḥ exist even if the text is not based on a Vorlage? And why is ḥ written quasi-regularly? Schweitzer writes:

Dass diese Verschreibungen nicht korrigiert wurden, lag m. E. auch daran, dass die mit 𓍋 [U23] geschriebenen Wörter aus der Alltagssprache verschwunden waren bzw. dass sie durch andere Wörter verdrängt wurden[fn. 173] und somit der genaue Lautwert nicht immer präsent war. (p. 144)

According to Quack, this motivation is not tenable. He writes:

Schweitzers Behauptung, hier seien Fehler nicht korrigiert worden, weil das Wort nicht mehr der gesprochenen Sprache angehöre und somit der genaue Lautwert nicht immer präsent war,[fn. 49] trifft in dieser Form sicher nicht zu. Das Wort mḥr “krank sein” ist zwar im Koptischen nicht mehr gebräuchlich, im Demotischen jedoch definitiv noch ausreichend gut belegt.[fn. 50] (pp. 278-279)

In note 50, Quack then lists evidence for the verb mr “to be ill” in Demotic. However, most of this evidence comes from literary texts. So here again we have the impure argumentation. What Schweitzer calls “everyday language” is certainly not congruent with what Quack calls “spoken language”. Once again, a straw man is set up! Nevertheless, one will tend to agree with Quack that the motivation Schweitzer proposes is questionable. Why should one use words in the textual production of demotic literary texts that one no longer knows and therefore misspells?

But how can one reconcile the phonetic value mr, which can be clearly proven in the inscriptions of the Early Dynastic Period, with the spellings with ḥ in the first millennium? Dear all, let me now take you into the world of toponyms. Al-Ayedi, Ancient Egyptian Geographic Dictionary. 2012, lists the following independent entry on page 775: Ssnw. He offers as spellings 𓋴𓋴𓈖𓏌𓅱𓊖 or 𓊃𓊃𓏌𓊖, among others. According to Al-Ayedi, it is the modern el-Ashmunin. The modern place name goes back to the Egyptian Ḫmn.w, cf. Peust, Die Toponyme vorarabischen Ursprungs im modernen Ägypten. 2010, p. 13. The name of the city was exactly the same as the Egyptian word for “eight”. Therefore, Ḫmn.w is also written with the digit for eight. Montet, Geographie de l’Égypte ancienne. Deuxième partie. 1961, p. 146, notes the following about the spellings of this city

Tardivement apparaissent les orthographes […] 𓋴𓋴𓈖𓏌𓅱𓊖 dont la lecture est identique.

Gauthier, Dictionnaire des noms géographiques contenus dans les textes hiéroglyphiques. Tome quatrième. 1927, p. 176, writes:

On rencontre aussi aux basses époques une série d’orthographes toutes différentes 𓋴𓋴𓈖𓏌𓅱𓊖, […], qui ne paraissent pas avoir été lues Sinou, mais bien Khmounou comme les autres […].

The spellings from more recent times are explained by the hieratic. There the sign for the eight resembles a 𓋴𓋴, cf. Jansen-Winkeln, Spätmittelägyptische Grammatik der Texte der 3. Zwischenzeit. 1996, § 42. However, not all spellings can be understood as direct misinterpretations of the hieratic. A 𓊃𓊃𓏌𓊖 still needs the intermediate step that a 𓋴 can become a 𓊃, because both signs have the same phonetic value s.

To summarize: Similarities in hieratic writing in the first millennium can lead to the reinterpretation of established spellings, and that these reinterpretations can in turn be the basis for further variations (in our example, 𓋴 becomes 𓊃). Hoffmann, Die Verwendung Hieratischer Zeichen in Demotischen Medizinischen Texten. In: Aspects of Demotic Orthography. 2013, pp. 38-39, lists many more examples:

- The well-known word wnm “to eat” is written in the Old Kingdom with the two signs 𓏘𓏘, which were later understood as q. This developed in the New Kingdom into an independent word qq, which appears in Demotic as kk and in Coptic as ϭⲱϭ, cf. Wilson, A Ptolemaic Lexicon. 1997, p. 1069; Peust, Das Napatanische. 1999, p. 182.

- The word ḫm “sanctuary” can be written 𓐍𓋉𓅓𓉐. The 𓋉 is interpreted over time as 𓊃. Wilson, A Ptolemaic Lexicon. 1997, p. 904 cites instances of alliteration with s. In this respect, then, an independent word zḫm has developed. The reinterpretation of 𓋉 → 𓊃 also affects the name of the city of Letopolis. The original Ḫm was later understood as Sḫm, as evidenced by the Greek rendering Ἀρνεβεσχῆνις of the demotic phrase Ḥr nb Sh̭m, cf. CDD s, p. 376.

- wꜣsi̯, which can be written 𓌁𓅱𓅪, mixes with ḏꜥm (𓌁𓅓𓅪) to form a wsm that appears in demotic texts, cf. Hoffmann, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros: Studien zum P. Krall und seiner Stellung innerhalb des Inaros-Petubastis-Zyklus. 1996, pp. 206-207, fn. 1054.

- In Demotic, the word for “wife” is originally ḥbsy.t, but later it is ḥm.t.

- The word zꜣ “son” is understood in filiations as pa “the of.”

Here, too, traditional spellings are reinterpreted. This even goes so far that, first, the new spellings find their way into the spoken language as new words and that, second, the reinterpretations caused by the hieratic script are partly also to be found in the demotic script. It would be too short-sighted to classify these new spellings exclusively as spelling mistakes. Rather, they testify to a productive handling of the millennia-old writing tradition. Here also lies the solution in the dilemma that 𓍋 certainly has the phonetic value mr, but nevertheless spellings with the single consonant sign ḥ are attested in the first millennium. As Schweitzer, p. 144 has shown, there is confusion of 𓍋 with other tall hieroglyphs. Then it is not unlikely that the 𓍋 - like the 𓏘 or the 𓋉 - was also subjected to reinterpretation. Interpretations internal to the script may have produced a new word with ḥ. Thus, it is not an “either mr or mḥr” but a temporal ordering. Classically one has to read mr, while in the first millennium it can also be mḥr. One has to interpret the 𓍋 according to the dating of the source. But this also means that one must accept the independence of the interpretations of the respective periods. It is not adequate to the sources if someone like Schweitzer wants to interpret the late evidence as errors. But it is also a failed endeavor when a researcher like Quack wants to invalidate the valid evidence from the Early Dynastic Period just because he knows evidence from the epoch he is familiar with that seemingly contradicts the findings from the Early Dynastic Period (an epoch in which - as can be clearly seen - he is not so familiar). We must not pit one epoch of Egyptian culture against another. Just as demotists do not like it when their field is not considered full-fledged Egyptology, so Early Dynastic Period researchers do not like it when colleagues like Quack do not take the material of this period seriously and want to explain away regular findings just because the later period sees it that way.

tl;dr

The phonetic value of 𓍋 is mr, not mḥr, as the evidence from the Early Dynastic Period clearly proves. Quack’s attempts to refute the evidence have all failed. Late spellings with single consonant signs for ḥ show that 𓍋 was reinterpreted in later times.

This work is marked with CC0 1.0 Universal